by Marspet Movsisyan

Few topics in Armenia spark as much anger, resistance, and hatred as the issue of LGBT rights. But if Armenia aims for a Western, European future, that sentiment probably has to change.

LGBT people in Armenia face insults, attacks and violence almost every day, often coming from their friends, families and even police officers. Most of these cases are, apparently, never made public, as LGBT issues remain one of society‘s biggest taboos. A heartbreaking example illustrates this: two years ago, in October 2022, Tigran and Arsen, just 16 and 22, took their own lives due to homophobic attacks, by jumping together from the 92-meter-high “Davtashen” bridge to their deaths. Shortly before, they had posted a photo together on Instagram with a caption “Happy end: the decision to share these photos and take the next step has been made jointly by both of us.” The Internet was flooded with comments like: “Finally they’re gone,” “Two fewer of them”. How is it possible that such young people feel so hopeless that they see no other way out?

The reason this issue came to light is because there are brave journalists in Armenia who report despite the risks of homophobic attacks. One such journalist is Anahit, who asked me not to use her photo or real name for security reasons. This further highlights the critical safety concerns faced by LGBT persons, as even journalists are unable to speak freely about the topic. In her personal life, Anahit is openly lesbian. At the same time, she experiences discrimination almost every day, including at work: “It took me months of work to be able to report on this [about Tigran and Arsen]. I was instructed to make it unclear that the boys were gay. My colleagues started calling my cameraman a ‘faggot’, because he was doing this story with me.” Anahit works for one of Armenia’s more progressive, Western broadcasters. She believes that a lot of people in the country are homophobic. And this is confirmed by the current state of discrimination and violence against LGBT people in Armenia: in 2023, 51 cases of hate crimes were registered, including 22 cases of domestic violence. However, these are only the registered incidents, as countless others go unreported due to victims’ fear of the police. Even in European countries like Germany, where LGBT victims are more likely to report to the police, the true numbers are often 10 times higher.

But what makes this topic a real powder keg?

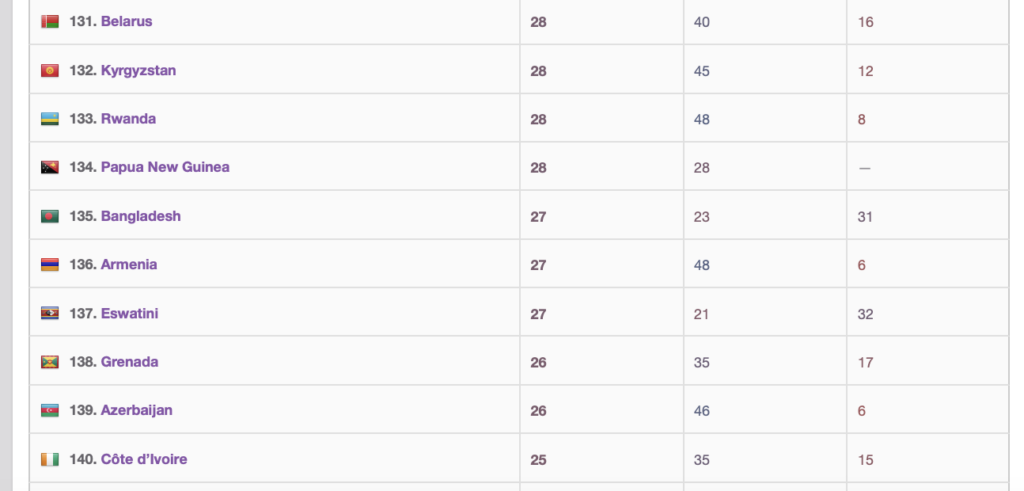

There are several reasons behind this. Armenia is a highly conservative country, strongly influenced by the church, which depicts a classic family model consisting of father, mother and child. On top of that, Russia’s influence and its constant anti-LGBT propaganda play a significant role, presenting LGBT people as a “threat to traditional Armenian culture.” And this is despite the fact that various scientific studies estimate that between 8-12% of people worldwide are said to belong to the LGBT community—a figure not created and disseminated by the LGBT community, but based on research. This suggests that a number of LGBT people live in Armenia too. It has long been known that sexual orientation is innate, and no one can choose or change it, with same-sex behavior also present in the animal kingdom throughout history. This is why many countries have banned so-called conversion therapies, which are supposed to “fix” or “cure” people’s sexual orientation. Armenia is currently ranked 136th out of 196 countries on the “LGBT Equality Index,” which evaluates the safety of LGBT persons, their rights, and other criteria, placing it in the lower-middle range. However, many LGBT persons in Armenia and outside remain hopeful.

The anti-discrimination law is on its way

By the end of 2024, the law titled “Ensuring Legal Equality and Protection from Discrimination” is expected to be passed. The idea behind the 36-page draft from the Ministry of Justice is quite simple: no one shall be discriminated based on their gender, skin color, social and ethnic origin or religious beliefs, and everyone is equal before the law. Such laws have been in place in Western countries for years. The term “LGBT”, however, doesn’t even appear in this draft, meaning there is no legal protection for those discriminated against based on sexual identity. And this is exactly what many LGBT persons in Armenia, international LGBT organizations and the European Commission criticized in July, calling for improvements to the law with regard to LGBT rights. The European Commission’s position goes beyond being merely a wish—it is a request directed to the Armenian government, which has been increasingly seeking closer ties with Europe since the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh, while distancing itself from Russia. Paruyr Hovhannisyan, Deputy Foreign Minister of Armenia, feels it might be premature to focus on LGBT rights in Armenia at this stage: “I would advise against bringing too many concepts to the table at the same time. Even in Europe the topic is fresh and still under discussion. But Armenians are quite open and flexible. I believe the law should come, but only when it is ready.” He is, however, uncertain when the right moment will come.

What about the youth?

For many young LGBT persons, the Internet or queer aid organizations like “Pink Armenia”, are often their primary sources of support. Mamikon Hovsepyan, a founding member and project manager at “Pink Armenia”, explained the challenges they face. He revealed their Yerevan office address only shortly before our scheduled meeting—for security reasons, he told me later. “Pink Armenia” has already been a target of verbal and physical attacks on several occasions, forcing them to change locations regularly. When asked why Armenian society is not yet ready to stand up for LGBT rights, Hovsepyan pointed to another crucial aspect, alongside the church and Russian propaganda: “The younger generation is much more open, but we have another problem here: at the age of 18, boys in Armenia are conscripted into military service. And regardless of how open-minded and progressive they might have been before, everything is ruined during their time there: they become aggressive and violent. And after completing their two years of service, they continue living like that.” Mental health for soldiers is rarely a topic of public discourse in Armenia, and psychological support options are limited. Added to that, many families simply cannot afford medical care for their sons. Is the system failing here? “Pink Armenia” steps in, offering psychological support, which is increasingly in demand. Yet, this alone is far from sufficient—state involvement is required. And if the state continues to neglect young people and fails to pass laws to protect their rights, many LGBT persons, no matter how much they love their homeland, will eventually choose to leave Armenia once they are old enough. Thus, it remains for Armenia to decide whether it is willing to accept this reality or whether it wants to create a future where everyone, regardless of skin color, origin, gender, sexual orientation, and more, is equal both before the law and within society.

Is there any hope for LGBT persons in Armenia?

Yes – at least that’s how Mamikon Hovsepyan sees it. He offers several reasons for his optimism: “Pink Armenia” has already won several legal disputes on behalf of queer individuals who sought help due to anti-LGBT attacks. He has also noticed a growing number of people on social media, speaking out in support of LGBT persons, or at least showing openness to the issue. Additionally, the LGBT community in Yerevan is organizing an increasing number of parties, given there are no LGBT bars. Another surprising, but significant development for the LGBT community is the fact that since last year, gay men have been allowed to donate blood. Considering that blood is always tested for infectious diseases, this step seems long overdue. Some LGBT persons, in turn, view Armenia’s efforts to strengthen ties with the EU as a glimmer of hope for the LGBT community in the country. There is hope within journalism too. Anahit, who faced mostly negative feedback and hate for her report about Arsen and Tigran, shared a story about a friend. His mother, after watching the report about the two boys, had said: “If the channel [Anahit works for] makes a report like that, then maybe it’s okay to be gay, after all.” This comment inspired Anahit to stay at her channel and continue working for change, even if it’s just in small steps.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Marspet Movsisyan was born in Artashat, Armenia in 1993 and has lived in Germany since 2000, currently in Cologne. He works as a freelance journalist on various projects in front of and behind the camera for the German public broadcaster ARD. He studied social sciences and did a journalism internship. His main topics are: origin, identity, migration, discrimination, racism and injustice.