by Anzhela Alekian

Nearly eight decades since the end of World War II, the world has yet to get rid of racism, discrimination, and xenophobia. People continue to lose their lives simply for being who they are, with ultra-right parties gaining popularity all over the world. But why would anyone support fascist ideologies after the powerful lesson history has taught us? Many would point to a lack of education and understanding of the mechanisms that lead nations to turn on one another and commit acts like genocide, driven by the belief that their race or nationality is inherently superior.

Throughout history there have been many genocides, but probably none has been studied and discussed as deeply as the crimes committed by Nazis. Living in Germany, one cannot but learn about the Holocaust even outside the school curriculum. There are multiple memorials, former concentration camps, museums, and monuments dedicated to the victims and survivors of this dark chapter. One can simply walk in Berlin and see the “stumbling stones” (small brass markers, known as ‘Stolpersteine’ in German) in front of houses, commemorating those who once lived there before falling a victim to genocide.

While it is undeniable that education on these matters is vital in every country, examining practices of a nation that once embraced Nazism, acted on it and decided to never repeat it again could be enlightening.

Immersing in the past

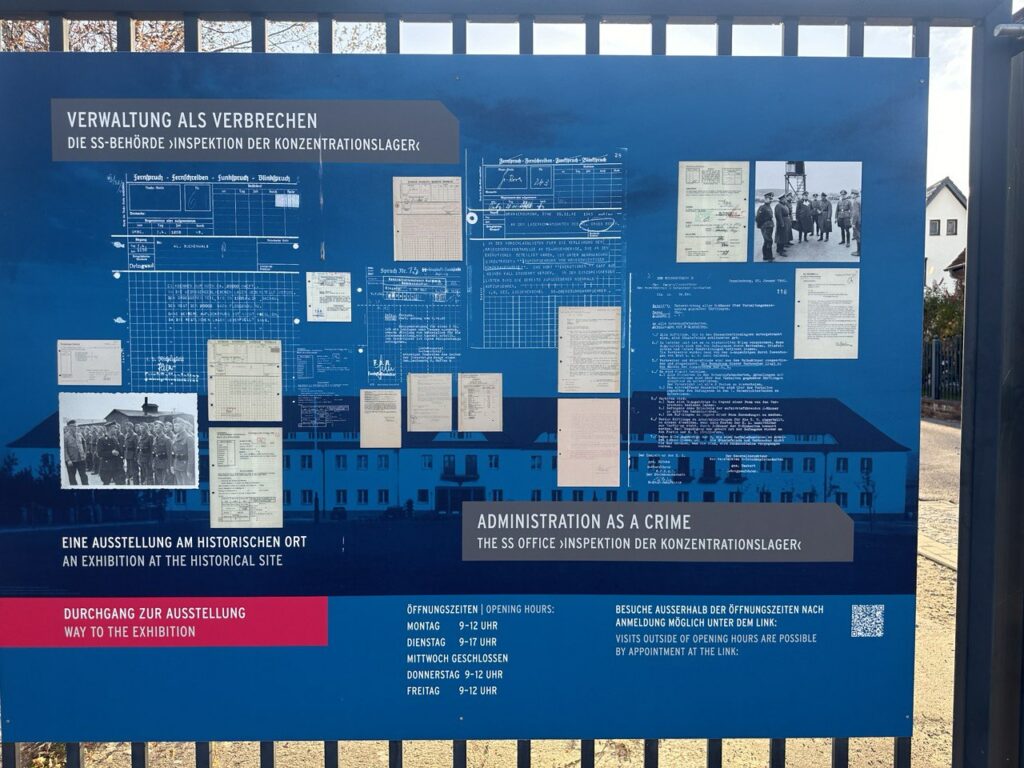

The manager of educational programs at Sachsenhausen Memorial and Museum Arne Pannen says the former concentration camp isn’t just a museum, it serves many purposes: for some visitors, it’s a place to remember, for others to mourn, and for many – to learn. Another important mission of the institution is training future police forces against discrimination. Interestingly, the Police Academy is located on the very grounds of the former concentration camp.

The memorial is located just an hour northwest of Berlin, in the town of Oranienburg. In the early 1930s, the first camp in Germanys’ largest region, Prussia, was established in Oranienburg, and in 1936 Sachsenhausen was built as a model concentration camp. Contrary to common belief, it wasn’t created as a death camp for Jews: its first prisoners were political opponents of the Nazis. Notably, residents of the town were told that these prisoners were being trained to be good citizens, so the town very much benefitted from the unpaid labor of former oppositionists. It was only later, as hate towards various groups became an official part of the Nazi ideology, that the camp expanded to include other groups – Sinti and Roma, criminals, queer people, Slavs, men from all the European countries occupied by Germany and, of course, Jews. While Sachsenhausen never became a death camp like Auschwitz, over 50,000 prisoners were killed there during WWII.

Sachsenhausen’s educational programs manager Arne Pannen believes that today every aspect of life in Germany is somehow affected by the years of National Socialism, making it crucial to thoroughly understand what exactly happened during those years and how something like that became possible. While the Nazi regime had a profound impact on Germany, its repercussions were felt far beyond its borders, which is why, as Pannen points out, there are many visitors coming to Sachsenhausen from the European countries that were involved in WWII.

“Most of our foreign visitors come from the UK, Denmark, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy, so mostly countries that were invaded by Germany. They all have their narratives about the victims from their countries, and they come here to learn more. But that’s not the only thing you can learn here. We try to talk to students visiting here about more general things like how discrimination works, or why people would put others in different categories, instead of seeing them as humans,” says Pannen.

He also stresses that the main focus of the memorial is to teach the youth, particularly those aged 14-15, the essential concepts of discrimination. Rather than shocking the visitors with graphic content and emotionally overwhelming items, the museum aims to create a space for reflection. The goal is to give visitors a chance to ponder over historic events, conduct their own research and leave with lasting impressions.

Another topic for discussion is the perpetrators, and their voluntary choice to work at the concentration camp. The memorial’s team worked hard to understand the reasons for their decision. As Arne Pannen explains, the guards in the camp were mostly young men from normal families, aged between 20 and 30, middle class, without higher education.

“Their motivation wasn’t only ideological: for many, it was a way to make a fast career, get a house, a wife, to stay away from the front, all while holding mighty position where they had power over people. It also provided them with a social rank that they would not have achieved through other job. It was an opportunistic way to build a career. So we show how the perpetrators got into cruelty, how they were forced to commit the first murder, after which they found it impossible to step back,” the expert notes.

Most visitors choose the basic 2-hour guided tour, but for those willing to spend up to 6 hours there is an opportunity to conduct research, work with documents, and touch the authentic objects that once belonged to inmates.

“Students should use these materials to delve into questions about the daily life in the camp, for example, whether inmates had toothbrushes. They have a bunch of materials and documents to find out details about daily life, the purpose of every object, and also how these experiences differed from their own daily lives․ So they can discover how inmates had to live here. It’s research-based learning,” says Pannen.

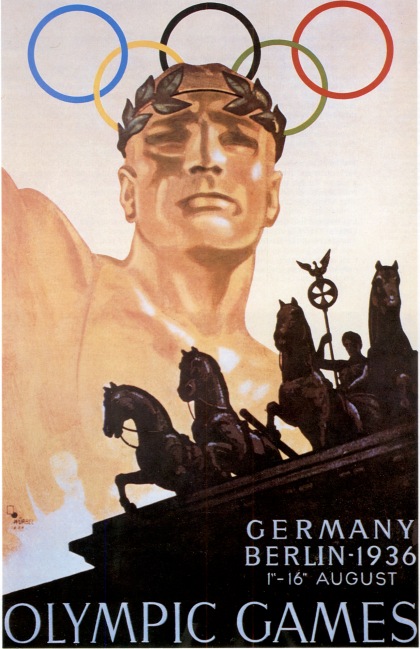

Among the workshops offered at Sachsenhausen, some focus on Sinti and Roma. Visitors may be shown some photographs to describe what they see. One example includes an image from the 1936 Olympic Games held in Berlin. People with an interest in sports may draw a connection between that notable event and the fact that the concentration camp in Oranienburg was being built in the same weeks. Thus, Sinti and Roma that lived in Berlin were forced into a special camp out of the city center, so that no visitor from abroad could see them.

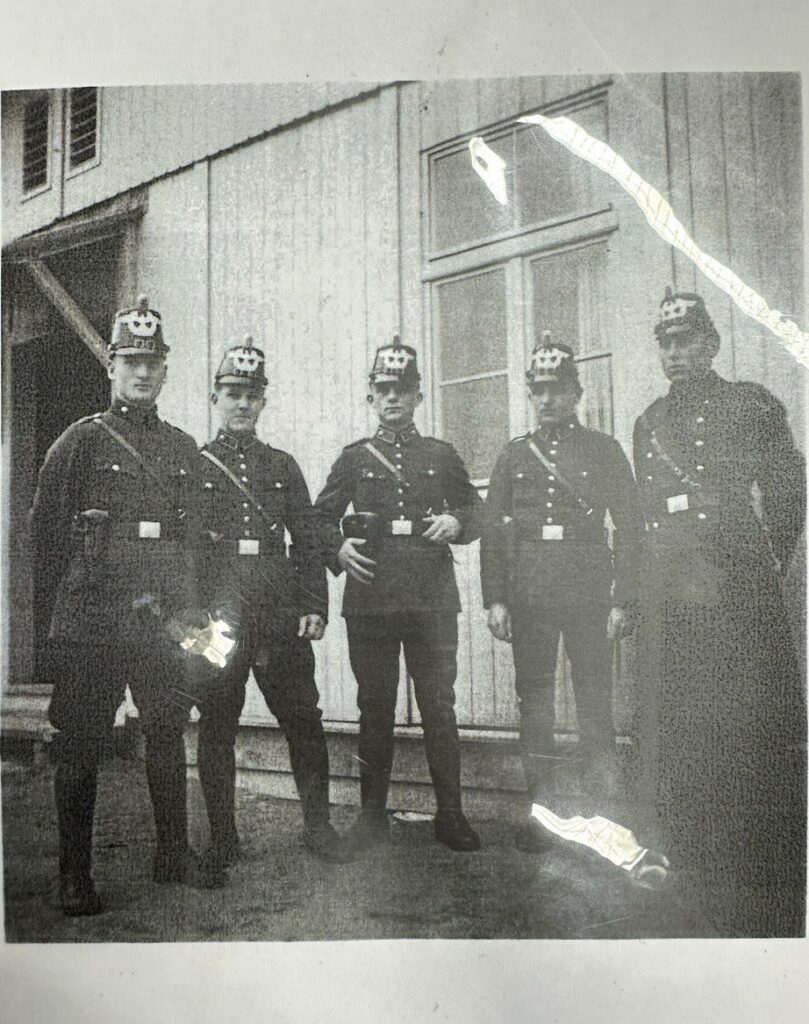

Another photograph portrays regular German policemen, which connects to the historical fact that the first guards in the Sinti and Roma camp were not SS soldiers but regular policemen.

The collection also includes modern-day images of Sinti and Roma, highlighting that these groups still face racism and may feel forced to flee the country, even so many years after World War II.

“When people look at these pictures, at first they don’t associate them with this place. But every picture has something to do with Sachsenhausen and persecution. This allows us to highlight that the line of persecution was not finished in 1945 and it’s still here today”, says Pannen. “We give kids an instrument to understand that social nationalism was a bad thing, and when you think about the situation today you will get the solution,” he adds.

The new digital world

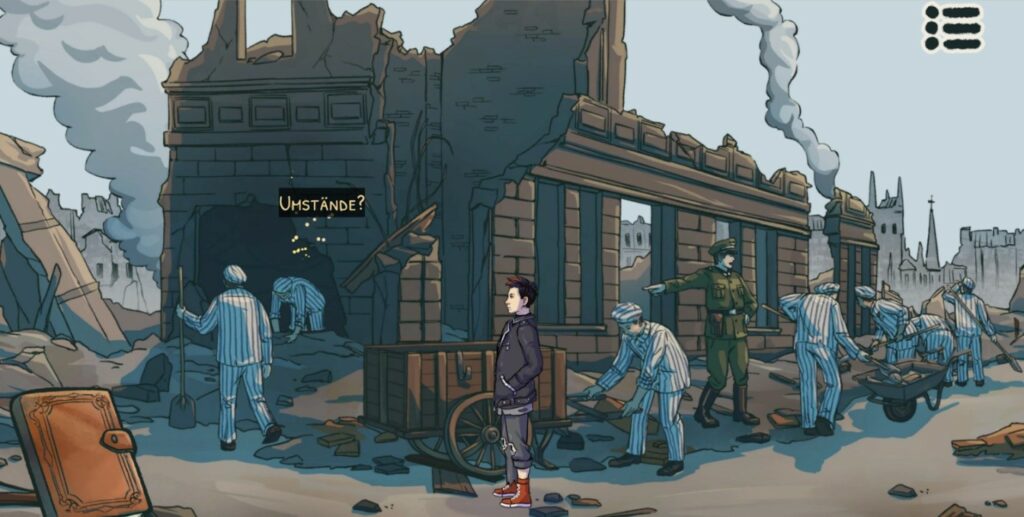

Jan Wilkens, who holds a PhD in Jewish Studies, is a program manager at the Alfred Landecker Foundation, named after Alfred Landecker, one of many victims of the Holocaust. The aims of the foundation are to remember the Holocaust, fight antisemitism and strengthen democracy. In contrast to Sachsenhausen, the Alfred Landecker Foundation also prioritizes the use of digital tools for Holocaust remembrance. Among the projects are video games designed to educate about the Holocaust.

As Dr. Wilkens explains, integrating Holocaust education in video games is a new approach taken after realizing that the old ways of educating about the Holocaust need to be enriched by new and digital approaches…

One of the games offers the following plot. You find yourself in a room, where you discover documents from your grandparents, such as a small box of old pictures showing them with Jewish friends, leading you to explore the history of your game-family to understand what happened to those friends.

“So, we aim to use these new tools to reach younger audiences. By creating this emotional connection, we try to engage children, or younger people more in the history of the Holocaust. If players go through the game, they may also dig deeper into their own family history. We use gaming as a tool to find a more emotional way of telling young people that the Holocaust has a connection to their families,” says Dr. Wilkens.

While measuring the impact of educational projects on such a sensitive topic is challenging, Dr. Wilkens believes these projects are of utmost importance. However, he stresses the need of prioritizing their quality over quantity.

While measuring the impact of educational projects on such a sensitive topic is challenging, Dr. Wilkens believes these projects are of utmost importance. However, he stresses the need of prioritizing their quality over quantity.

“Students usually start learning about the Holocaust in history classes, continuing in high school and later while getting higher education. We also have, for example, German language classes, which involve reading books about the Holocaust or books created during the Holocaust. Almost in every social science class, you encounter topics related to the Holocaust. But eventually students start saying, “It’s just too much. We can’t hear about it anymore.” I believe schools have to figure out a way to teach children about the Holocaust and history without overwhelming them with historical facts. And such more practical, more emotional approaches to the topic could help. For instance, some schools dedicate a week to having students explore the Jewish history of their own town. I think this is far more effective than just teaching students about the Holocaust in the classroom,” says Dr. Wilkens.

As a person with experience teaching the history of the Holocaust to schoolchildren, he also shares the nuances that should be taken into account while working with a class.

“If you have a room with Jewish and non-Jewish students, the chances are really high that non-Jewish students don’t know anything about their personal or family history in World War II, while it’s highly probable that Jewish students know everything about their own history. Therefore, you have to be very careful about that. You shouldn’t put Jewish students in a position of having to share the experiences in their family history with the class, because they are perceived as representatives of the victims,” Dr. Wilkens points out.

Another key point to keep in mind, according to the researcher, is ensuring that German students in class do not feel blamed or under attack for the events that happened long before they were born. “Students very often feel compelled to defend themselves, which is not really the goal of the whole educational program or the debate. It’s more about responsibility, it’s more about learning and prevention,” says Dr. Wilkens.

The Holocaust has been studied in Germany since the late 1980s, with educational programs beginning in the 1990s, which means there is space for development in this area. Dr. Wilkens advocates for more inclusive approaches, emphasizing that research and education should extend beyond the Holocaust and the persecution of Jews alone to include other marginalized groups like Sinti and Roma, Slavs, queer persons and disabled people. As a researcher, he also suggests that Germany needs to confront its own colonial past, pointing to dark chapters like the genocide in Namibia.

And while Germany continues to struggle with these complex historical issues, researchers and politicians seem to fully acknowledge the problems and demonstrate willingness to find effective solutions. This awareness sets a positive example suggesting that more nations and individuals should combine their efforts to ensure hatred and discrimination will never be part of anyone’s identity in the 21st century.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Anzhela Alekian is a Yerevan based journalist, editor and communications manager. She has over 15 years of experience in the media field. Among her interests as a journalist are international relations, education and science.

Anzhela Alekian is a Yerevan based journalist, editor and communications manager. She has over 15 years of experience in the media field. Among her interests as a journalist are international relations, education and science.