In the wake of Azerbaijan’s September attack on Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia is in a state of shock-induced paralysis. Prime Minister Pashinyan is weaker than ever, while at the same time the country has to integrate over 100,000 refugees. And looming above all is the threat of a new war.

by Dominik Kalus

In order to visualize the war, visitors of the Armenian capital Yerevan only have to hop in a taxi for a short ride: the Yerablur military cemetery is located on a hill outside the city center with its hip cafés. A sea of Armenian flags flutters over the graves, with mourners occasionally standing amidst the extensive rows, laying flowers and weeping. The gravestones show portraits of dead soldiers: young faces, many of whom were barely 20 years old when they died in the war against Armenia’s neighbor Azerbaijan. A dirt track leads to the newest graves, the mounds above them covered in flowers. They were only dug a few weeks ago.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan and Armenia have fought several times over the Nagorno-Karabakh region, which belongs to Azerbaijan under international law – but was populated by Armenians and is of central importance to the Armenian people. In 2020, Azerbaijan captured the majority of the Armenian-controlled territories in the so-called 44-Day War. A fragile ceasefire was negotiated with Russian mediation, and Russian troops were supposed to ensure compliance. However, Russia only stood by and watched as Azerbaijan launched another offensive in September 2023 and took control of the rest of the region. Around 100,000 Armenians – almost all of those who remained there following the 2020 war – hastily left their homes for fear of Azerbaijani violence.

Since then, Armenian society has been in a state of shock. There is great anger towards Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan; many Armenians see him as a failure and traitor who is responsible for the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh through inaction and miscalculations. Pashinyan had already gambled away the trust of the population during the 2020 war when he hid the catastrophic situation on the front from the public. But there seem to be no alternatives in sight – not least because no one is taking on the ungrateful task of managing the current situation. The country with a population of 2.8 million has struggled to accommodate the refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh – it is still unclear how they are supposed to live and from what.

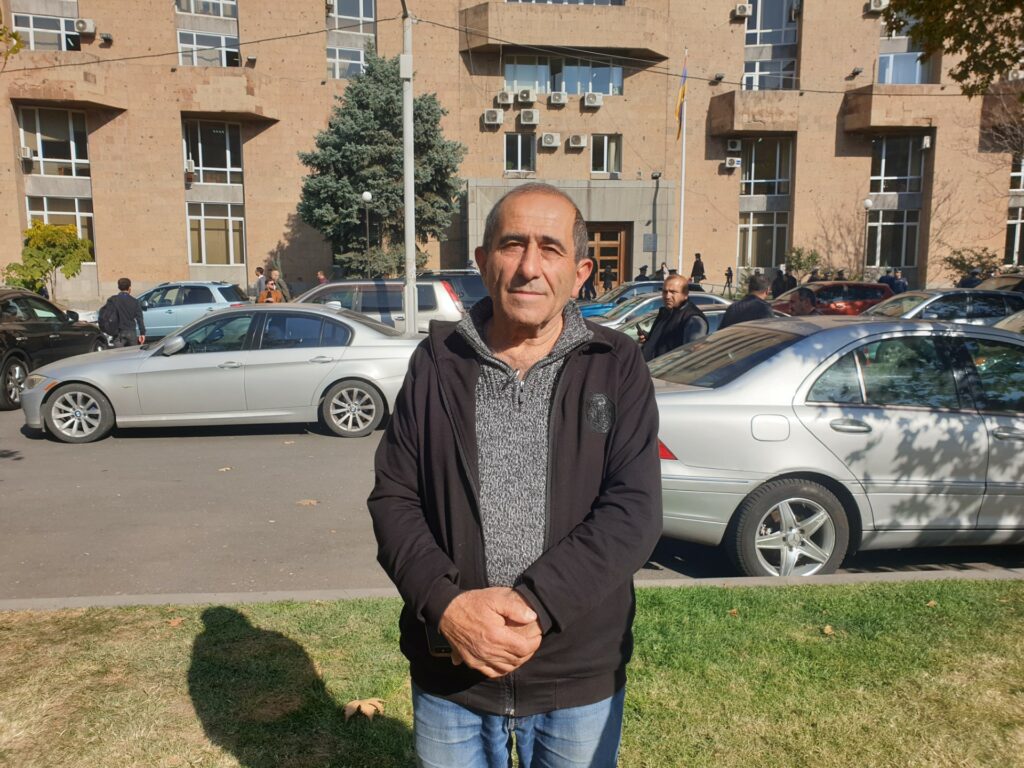

“I have fought in three wars and now I am treated like a nobody,” says a man who introduces himself as Viktor. Together with around 200 other Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians, he is standing in front of the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs in Yerevan on a November morning. They have come to show their anger to the Armenian government. The government is not paying the pensions they are entitled to, says 64-year-old Artur Chalyan. The money is urgently needed here; all he managed to take with him from Nagorno-Karabakh were clothes. They, a family of sixteen, live in four rooms. Yerevan doesn’t offer him much hope for the future – but he has no hope of returning to Nagorno-Karabakh either. “There is no one there who can guarantee our safety.”

The small democracy of Armenia is in an extremely unfavorable position on the geopolitical map. The enemy Azerbaijan to the east, Turkey to the west, which to this day denies the genocide committed against the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. To the south, internationally isolated Iran. The role of the protecting power traditionally fell to Russia, which demanded unconditional loyalty for this service. Armenia’s increasing inclination towards the West, the strengthening of democratic institutions and civil society, its recent ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court – all of this was greeted with disfavor by Russian President Vladimir Putin. Many Armenians see it as a punishment from Putin that Russia allowed the Azerbaijani offensive to take place in September. Since then at the latest, Russia is no longer considered a reliable partner in Armenia either.

Armenians, especially the young people in the capital, would prefer to orientate themselves completely towards the West. At the same time, most people realize that this is hardly feasible: Armenia’s economy is heavily dependent on Russia, and its energy supply is virtually in Russian hands. Pashinyan, thus, has few options other than to continue his unsteady course: provoke Russia as little as possible while leaving open the channels to the West, essential both morally and politically to the country.

The EU has sent an observer mission to Armenia to monitor the border with Azerbaijan and document incidents. France has announced that it will help Armenia with arms deliveries. And at the beginning of November, Germany’s Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock travelled to Armenia and then to Azerbaijan to mediate. At the same time, the EU has also lost trust. Before its attack in September, Azerbaijan had starved out Nagorno-Karabakh for nine months through a blockade – without any significant reaction from Europe, which continues to receive gas from the country’s autocratic regime.

European attempts at peace have so far come to nothing. Azerbaijan accuses the EU of taking sides with Armenia while Yerevan blames Azerbaijan for blocking the negotiations with their maximalist demands. Among other things, Baku wants to gain access to its exclave of Nakhichevan via Armenian territory. “Azerbaijan is not interested in normalizing relations because it now has the upper hand,” says Armenian analyst Areg Kochinyan. Since the 1990s, the balance of power between the hostile states has reversed. Benefiting from the oil and gas trade, Azerbaijan has armed itself and cemented a strong partnership with Turkey, a powerful ally providing substantial backing.

There is great fear in Armenia that Azerbaijan will use force to establish the corridor to Nakhichevan while the world is distracted by the wars in the Middle East and Ukraine. Armenia would have little to counter an attack; the capabilities of the Armenian army largely diminished in the 2020 war. This is one of the reasons why Pashinyan handed over Nagorno-Karabakh without a fight in September.

But not all Armenians want to simply surrender to helplessness. In a run-down hall in Yerevan, a mosaic from Soviet times and an Armenian flag on the wall, 30 men and women stand in two rows. Shortly afterward, they will be crouching in front of the hall with dummy rifles amidst trees and car parks, practicing aiming and taking cover. Before that, 20-year-old Nané, with dark, wavy hair, wearing camouflage trousers, leads a tour of the area. “I felt so helpless in 2020,” she says. Since coming here, she feels stronger. VOMA, a non-governmental defense movement, offers courses on first aid, fitness and survival, as well as military tactics and basic weapon handling, with an average daily attendance of around 100 civilians.

One of them is 22-year-old David. “Every Armenian has relatives who were killed or wounded in a war. That’s why we’re here,” he says. He has tied up his long hair and trimmed his fine beard short. He fought for a month in the 2020 war, but claims he didn’t learn much. That’s the reason he’s attending a three-month intensive course here. David has no plans for the future – the world situation is too “messy” for that. He thinks a lot about his friends who are currently stationed on the border. “The war could come any day.”

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Dominik Kalus is a political journalist, covering domestic and international topics for Berlin-based newspaper DIE WELT and the southern German radio station BAYERN 2. He is especially interested in (Middle) Eastern European and former Soviet countries. He studied in Passau (Germany), Wroclaw (Poland) and Moscow (Russia).

Dominik Kalus is a political journalist, covering domestic and international topics for Berlin-based newspaper DIE WELT and the southern German radio station BAYERN 2. He is especially interested in (Middle) Eastern European and former Soviet countries. He studied in Passau (Germany), Wroclaw (Poland) and Moscow (Russia).