by Benjamin Brown

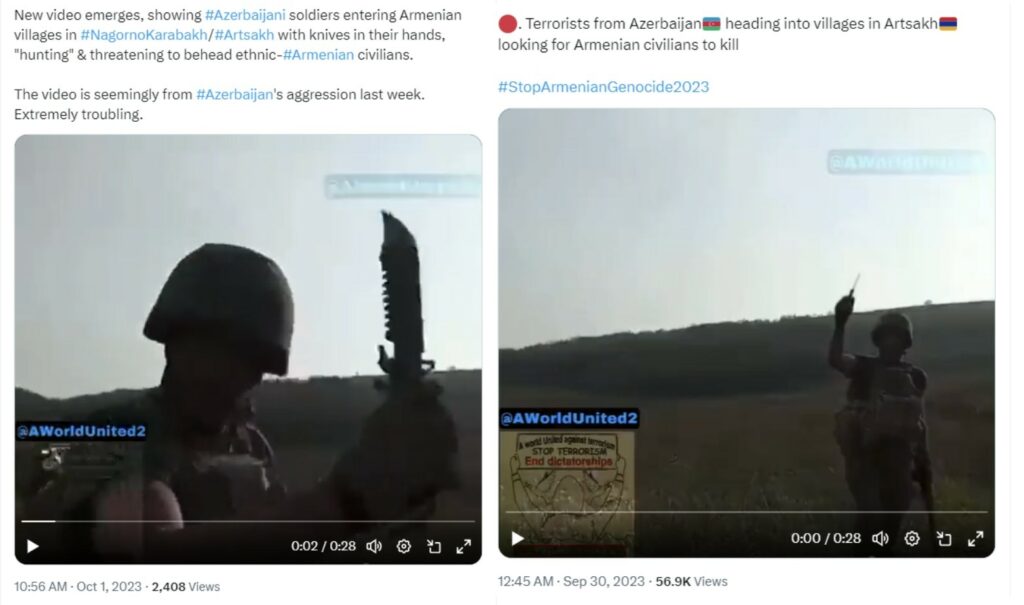

It was a scene many had feared. In September 2023, as the forced expulsion of around 120,000 ethnic Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh was in full swing, a video was circulated online showing a soldier in an Azerbaijani uniform brandishing a knife while menacingly threatening to decapitate inhabitants of the enclave.

Further footage began being spread across social media showing Azerbaijani troops threatening atrocities against civilians and desecrating cultural heritage sites, in particular churches, in the ethnic Armenian enclave.

The video of the soldier waving the knife, captioned as having been filmed in September 2023, was shared particularly widely online as evidence of Azerbaijani war crimes in the region.

A separate video played on another widely echoed fear. Showing soldiers in Azerbaijani uniforms desecrating an Armenian church in the self-declared Republic of Artsakh, the video – also frequently labelled as having been filmed in September 2023 – appeared to validate concerns that Azerbaijani forces would destroy Armenian cultural landmarks.

Impact of Disinformation: Fueling Fear and Uncertainty

Local leaders and Armenian politicians had warned that with the self-declared Republic of Artsakh militarily defeated, such scenes would likely follow. The footage many social media users eagerly shared was seen as proof that those fears had been legitimate.

The footage being circulated was, however, old.

The use of open-source intelligence (OSINT) tools, including the analysis of metadata and reverse image search, showed that the video of the soldier with the knife had been circulating online since at least 2021 and was likely recorded during the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War (also known as 44-Day War) the previous year. Similarly, an analysis of the video in the church yielded analogous results, indicating its upload long before September 2023.

The decade-old conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh had been marked not just by military confrontations but also by a destructive battle waged in the information space, fueled by misinformation and disinformation efforts.

These campaigns – concerning misinformation, false information that is often shared without intending to deceive, and disinformation, deliberately false information spread with the intention to deceive or manipulate – have sought to shape public opinion, manipulate perceptions, and intensify fear and anxiety among civilians, often through the dissemination of falsified or misleading footage on social media platforms.

Armenia’s Media Landscape and the Erosion of Trust

While OSINT tools showed the videos to be old, the damage was done. The footage was shared by accounts, including those with large followings both in Armenia and the Diaspora, and, in at least one case, even by an Armenian government official. It had intensified widespread fear over the treatment of civilians and Armenian cultural heritage sites in the region.

With very real implications: Aren Melikyan, an Armenian journalist who has covered Nagorno-Karabakh for outlets including CNN, believes that the dissemination of unverified news, mainly on social media, further fueled fear amongst residents, leading to a “general atmosphere of panic and anxiety” in September 2023.

Unlike in similar instances in 2020, there was no evidence to suggest that the footage was being circulated in an orchestrated manner that would hint at an organized disinformation campaign. Instead, Areg Kochinyan, President of the Armenian “Research Center on Security Policy”, believes that a “lack of media literacy” and “panic” led to the sharing of fake news by prominent Armenian figures.

Such phenomena are not limited to Nagorno-Karabakh. Indeed, the current war in Gaza has presented similar challenges to social media users and, particularly, those working on visual investigations, with old footage being circulated, sometimes not even originating from the region in question. Footage from Syria, for example, has been widely shared across social media platforms, being attributed as stemming from Gaza.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the sharing of unverified, outdated or mislocated – and in some cases outright false – footage presents an ever-increasing challenge to journalists and the general public.

OSINT: Unveiling Deception and Countering Misinformation

Misinformation had been on the radar of many journalists reporting on Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023, after the 2020 war had been marked by intense disinformation campaigns originating both within and outside of Armenia.

In fact, in 2020, disinformation publicized in Armenia – both stemming from the Armenian defense ministry and Azerbaijani social media channels – had become so widespread that it led to a breakdown in Armenians’ trust in their media landscape, according to Melikyan, with much of both Armenian and Azerbaijani coverage of the war in 2020 “completely based on misinformation.”

“That is also the reason why the trust in the media in Armenia shrank dramatically after the war,” Melikyan added. He pointed out that “rare independent voices who tried to occasionally oppose the general narratives were targeted and discredited” in Armenia, something echoed by other Armenian journalists.

Unlike in 2023, during the 44-Day War, much of the disinformation circulating on social media appeared to stem from well-organized campaigns believed to originate in Azerbaijan and Russia.

Disinformation spread in 2020 was used by Azerbaijan to “target the population of Nagorno-Karabakh […] and provoke panic within the population,” Melikyan said. While Armenian media had approached such information critically, many outlets had “easily fallen into the trap of manipulated information” spread by Armenia, according to Melikyan, with such disinformation frequently employed to obscure the vulnerable and chaotic situation on the battlefield.

With social media, in particular, awash with contrasting claims, it was journalists using OSINT techniques who succeeded in debunking disinformation spread in 2020.

One investigation by Bellingcat, an organization that holds a prominent position in the OSINT community and is renowned for its investigative work utilizing digital tools and open-source information to uncover and verify facts in conflicts, geopolitics, and disinformation campaigns worldwide, proved a particularly successful example of countering disinformation originating abroad.

With the war ongoing and growing speculation over the involvement of Russian mercenaries, including from the Wagner group, a Telegram channel linked to Russian mercenaries began sharing hints at Russian guns-for-hire in Nagorno-Karabakh. After initially sparking rumors by sharing a song, which included references to Stepanakert, the capital city of Nagorno-Karabakh, the account posted two photos: one of a plane and one of a mountainous landscape. The intention was clear: the channel was suggesting that Russian mercenaries had made their way to the front lines in Nagorno-Karabakh.

In an investigation for Bellingcat, Armenian journalist Karineh Ghazaryan employed OSINT techniques to debunk the claims. The photo of the plane, she found, was old. Meticulous geolocation enabled her to determine that the mountainous landscape did not show Nagorno-Karabakh – or even the region. The photo, Ghazaryan discovered, had instead been taken in Syria.

While this prominent case of disinformation originated in Russia, for many other cases, Armenian journalists merely had to look across the border, to neighboring Azerbaijan.

Countering Azerbaijani Disinformation with OSINT Tools

A notable example of disinformation being circulated by Azerbaijan in 2020 was debunked by Vahe Sarukhanyan, an investigative journalist with Armenian independent investigative outlet Hetq. Again, social media was utilized to spread false claims.

With the battle for the Nagorno-Karabakh city of Shushi raging, footage began circulating on social media showing an Azerbaijani flag atop what was described as the fortress of Shushi. Except, it wasn’t.

Employing geolocation tools, Hetq’s Sarukhanyan showed that the building in the video was, in fact, a mosque in the Azerbaijani city of Gabala rather than the fortress in Shushi. In a video posted shortly afterwards, a fortress in Baku was made out to show Shushi.

Highlighting distinct architectural differences between the actual Shushi landmarks and the misrepresented locations in Azerbaijan, Sarukhanyan used open-source information to debunk the claims that Azerbaijan had raised its flag over Shushi.

With the disinformation likely disseminated to boost Azerbaijani morale, shape public opinion, and create psychological pressure, Sarukhanyan and his colleagues showcased the value of OSINT in conflict reporting.

For Sarukhanyan, the efforts to debunk disinformation did not end with the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. More recently, in August of 2023, he used publicly available sources to counter a false claim by Azerbaijan’s defense ministry that self-declared Artsakh forces had used radio-electronic warfare (EW) to disturb the use of GPS by Azerbaijani civilian aircraft.

Using flight tracking sites to show that the aircraft in question were transmitting regular GPS data in the timeframes in which they were allegedly being jammed, Sarukhanyan managed to “debunk the claim by Azerbaijan that Artsakh forces were targeting Azerbaijani planes thousands of kilometers away.”

Implications beyond Nagorno-Karabakh

With Nagorno-Karabakh under a strict blockade when Sarukhanyan published his investigation in August and access to the region virtually impossible, the use of publicly-available sources had allowed journalists an opportunity to investigate claims from the region – further underscoring the value of such techniques in conflict zones.

It had been this precise lack of access, which had made traditional forms of conflict reporting largely unviable in September 2023.

“Unlike the 44-Day War, when hundreds of journalists and foreign reporters were in Nagorno-Karabakh and had the opportunity to keep track of the developments, investigate and fact-check the situation on the ground, in 2023, the reporting on the conflict was limited to the view of the Azerbaijani sources – heavily controlled by the state, which made the independent coverage impossible,” Melikyan said.

His thoughts were echoed by Sarukhanyan, who believes that one of the key reasons disinformation was “spread over social media and shared widely, even by people living in Armenia” was due to the fact that most of the footage coming out of Nagorno-Karabakh was “being published by the Azerbaijanis – this is what is circulated.”

With journalists unable to access the region and local reporters being forced to flee after the end of the military action, unverified information was disseminated widely. And yet, despite the unique situation of the blockade in the run-up to the hostilities in 2023, the lessons from Nagorno-Karabakh apply to regions further afield.

Conflicts have traditionally been plagued by misinformation and disinformation campaigns, an issue that has been exacerbated by the widespread sharing of outdated, misattributed, or entirely false footage capable of perpetuating widespread fear and shaping narratives, especially in conflict zones where access for independent reporting remains constrained and unreliable.

The challenges persist, emphasizing the critical need for enhanced media literacy and consistent, transparent reporting, making use of OSINT techniques to counteract the enduring impact of deceptive narratives on public perception, a vital necessity that became especially evident in Nagorno-Karabakh.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Benjamin Brown is a freelance journalist based in the UK and Germany. Benjamin previously studied at the University of Oxford, Munich’s LMU and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He now mainly works on CNN’s news desk and investigative team, where he has spent the past 16 months largely covering the war in Ukraine. Benjamin focuses, in particular, on conflict and war crime investigations through open-source intelligence (OSINT).

Benjamin Brown is a freelance journalist based in the UK and Germany. Benjamin previously studied at the University of Oxford, Munich’s LMU and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He now mainly works on CNN’s news desk and investigative team, where he has spent the past 16 months largely covering the war in Ukraine. Benjamin focuses, in particular, on conflict and war crime investigations through open-source intelligence (OSINT).