by Sofi Tovmasyan

At the end of a long, narrow street, against the backdrop of a black roof, bold blue letters form the word “RIAS” – a reminder of the past, hinting that the building of Germany’s public radio is just around the corner.

Not long ago, before the reunification of the country in 1990, RIAS (German: Rundfunk im amerikanischen Sektor, English: Radio in the American Sector) radio station in Berlin was the only source of information for residents of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), especially for Berliners, who wanted to know what was happening on the other side of the Wall – in the American, British, and French sectors of the city.

At RIAS, there is someone who remembers the events and challenges he and his colleagues have faced with remarkable clarity. Welcoming us into the building is none other than Olaf Oelstrom – a man with dark blue eyes, expressive gestures, and a calm and grounded tone.

Germany’s public radio has been 66-year-old Olaf’s first and only workplace. He was 22 when he first arrived here, becoming the youngest radio speaker in what was then the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany).

Olaf not only recalls that day with great clarity but also reflects on the changes in the station’s work culture, his past colleagues, and all the fascinating incidents that took place during his shifts.

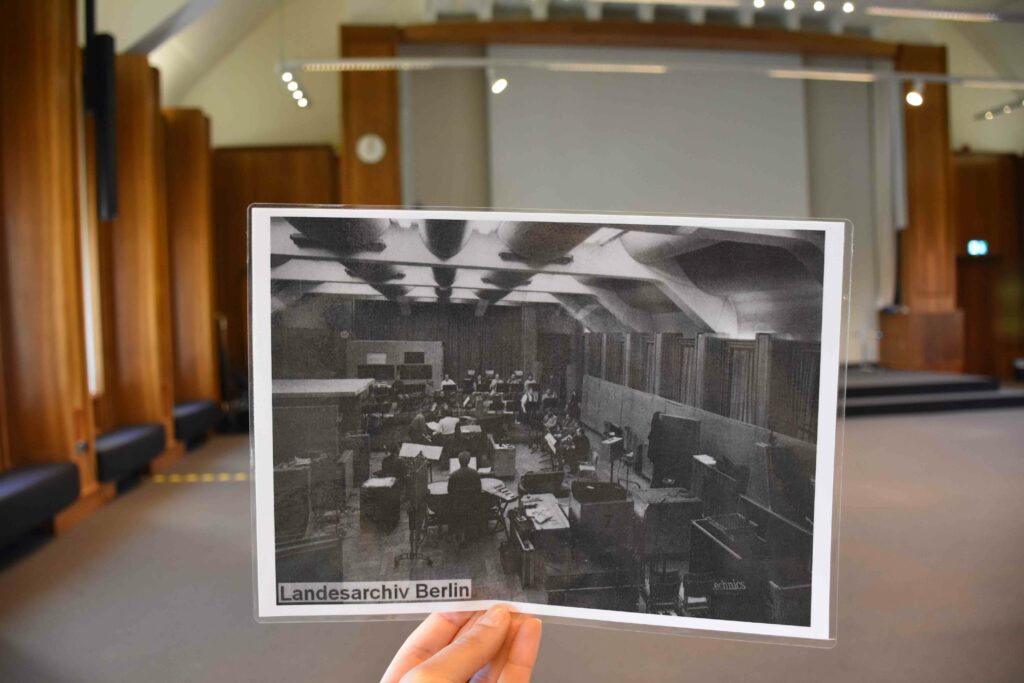

As we climb the spiral staircase from one floor to the next, Olaf is carrying a dark brown bag in his right hand. That bag holds an entire record of his memories – photos bearing witness to his years of experience.

There was a time when working here was a dream for Olaf. Now, he moves through the radio station as if it’s his own home; no door here is closed to him. It’s he who greets visitors, guiding them through the station’s history.

Colleagues, both old and new, who always receive a warm smile and greeting from Olaf, often ask him, “What was the station like back then?” And like them, I, too, share their curiosity.

– Olaf, do the young people working at the radio station realize that you are a walking history?

– Probably (he laughs). I’m often asked about how we worked back then, especially during the Cold War years. Mostly, I tell anecdotes about my former colleagues from that time, many of whom are no longer here. Although, when I first entered the world of radio, they had already been working for what felt like a thousand years.

– Do you remember the first time you came to RIAS?

– I’ve loved listening to the radio since I was a kid. I knew all the speakers and shows by heart. So when I saw a job advertisement at 22, I decided to give it a try. It was February 1982. The moment I came for the interview, it felt as if something magical was happening. I took the elevator right here (he points to the elevator on our left), went up to the third floor, walked down a long corridor to the studio we were just in. I was looking at the lights and signs on both sides, and I remember how quiet it was. I wanted to open every door and see what was behind them. I was truly impressed.

– Now, you can open those doors whenever you want.

– True. I had so much excitement and love for radio and broadcasting. Initially, I applied for the production assistant position, but the interviewer handed me a newspaper and asked me to read it aloud. After hearing my voice, he praised it and asked whether I’d be interested in working as a speaker. Of course, I agreed.

– Is getting into radio today just as easy as it was back then?

– No, now everyone has specialized education and comes to the radio already equipped with necessary knowledge. As for me, my first time on air was during a night shift—at 2:30 AM. One of my colleagues, who was showing me around, suggested I start at that hour. I guess they thought, “He’s a newcomer; maybe he won’t do well, better to have him start at night.” But it went so well that I ended up staying on the microphone until dawn. My colleague later told me I had done a great job. I still remember walking home from the radio station at 7 AM, feeling so happy.

– What’s the most interesting or important piece of news you’ve delivered to radio listeners during your 40 years on the job?

– Again, I was on the night shift. Well, you know how it goes—endless cups of coffee. It was the 1990s, around 1:30-2:00 in the morning, and I was reporting on the first Gulf Crisis (Referring to the Iraq-Kuwait war that started in 1990).

Also, it was always big news when someone tried to cross the Wall into West Berlin. Many people lost their lives that way.

And there’s something else I recall from before I started working: on June 17, 1955, there was a workers’ protest in the city because the authorities wanted people to work longer hours to support the economic growth, but without offering any extra pay. Thanks to the radio news, people were able to find out in which parts of the city the protests were taking place and would head there to join in. So radio has always played a big role not only in informing but also influencing the course of events.

– What was it like being a journalist during the Cold War? Wasn’t it dangerous?

– One day, when I was still a coordinator and hadn’t hosted my first show yet, I had prepared the script for the evening program and was just sitting there, waiting for the speaker. But he never showed up. I had to broadcast something else instead.

– Where did he disappear to?

– That colleague of mine lived outside Berlin, and every day when entered the city for work, he had to carry a special permit, which he would need to show if they stopped him. That time, while driving on the highway, the East German police stopped him. When they learned he was a RIAS speaker and heading to work to deliver the news, they said, “No, no,” and refused to let him pass. Working here in the context of the GDR was also a serious responsibility because people were in an information famine. Soviet newspapers only told what the regime thought was right, which is why people also wanted to listen to us—to understand what was happening on this side of the Wall. Even though the Soviet Union had set up around 80 devices across the country, which distorted our broadcasts.

Olaf Oelstrom plays an archival recording: a sharp, piercing static crackle can be heard, mixed with the speaker’s voice.

– Can you hear that? That’s how our broadcasts sometimes reached the listeners.

– Have there been other challenging moments in your work?

– The most challenging part began when Germany was reunified. The GDR team came here to join us, and it felt as if we were people from two different worlds. The working styles, the topics we wanted to cover, even the music we listened to, were all different—we loved listening to American bands, while they, for instance, preferred Tchaikovsky. It’s hard to say exactly what was the most difficult. It was a small team, but they quickly learned how to promote democratic values in their broadcasts. The issue was that the RIAS people—the Western speakers—approached things with a sense of superiority, almost like they were saying, “Come, we’ll show you, we’ll teach you the right way to work,” almost implying, “Look, we’re from the free side, while you’re under the influence of the Eastern bloc.” The hardest part was building human relationships. You see, the Eastern team members never walked alone in the building; they always moved in small groups. They didn’t quite feel at home here.

– Have the work style, the people, and the culture changed a lot?

– When I was a speaker, I was just a speaker. Now, they do everything, it’s like a one-man show. Along with digitalization, a lot has changed technically as well. Twenty or thirty years ago, there were about 20 people on a shift during a broadcast; now it’s just 3 – the speaker, the sound engineer, and the security staff. The number of staff has really decreased, and also now many people work from home. We used to have one big room where we’d gather during breaks, have lunch together, drink coffee, and sometimes even beer (he laughs), and discuss what we were writing and what we were going to broadcast that day.

– Do you miss that communication culture at the workplace?

– Yes, I do. It creates a sense of loneliness, even for the speakers who work almost alone most of the time. The fact that many people work from home makes the building feel quite empty, bringing a sad feeling.

– Have you ever considered leaving the radio?

– That only happened once. I had got divorced, and it was a very difficult period for me. I felt like leaving this city and starting a new life. I applied to another organization in southern Germany, got accepted, but I didn’t go.

– What held you back?

– I realized I couldn’t and didn’t want to leave the radio; it’s an emotional place for me, and in some ways, even a romantic one. When I was young, it didn’t matter what was going on outside these walls, whether people were asleep or awake—this was a place of constant presence. People here are always on the move, there’s always something being broadcast, and they always know what’s happening. That’s why this place is truly special to me. It always had that sense of presence. With the rise of digitalization, however, that feeling has slightly faded. Now, a radio host can sit alone all night, while before, radio was a place of energy, experience, and emotional exchange – this was all part of the broadcasting culture.

– You showed us the studio where you used to work. How do you feel every time you step into that room?

– It feels like a small journey through time. But I don’t feel sad; I only feel great joy and warmth. When I retired and started giving tours to guests, I realized it was the right time to leave. So much has changed, and I don’t think I would feel as comfortable here now as I did when I was younger. So looking back on the old times from a distance only brings positive memories.

– What was the reaction of your colleagues when you retired?

– Now, someone else has taken my position, and I’m happy that I can make space for new people, for the younger generation. I’m confident that even the existence of artificial intelligence will not hinder the work of radio hosts, because people will always need to hear a real, human voice, one that conveys emotion.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Sofi Tovmasyan is a journalist and PR specialist who studied in Yerevan, Armenia. She is a freelance reporter focusing mainly on human stories based on the psychological, socio-economic, and emotional well-being of refugees, who have suffered the most due to conflicts and wars. She is also currently working on a series of video stories on war crimes by searching for and telling the stories of people who have experienced them personally. Her main focus is to raise difficult and painful topics, thereby contributing to increased public awareness and the emergence of positive changes.

Sofi Tovmasyan is a journalist and PR specialist who studied in Yerevan, Armenia. She is a freelance reporter focusing mainly on human stories based on the psychological, socio-economic, and emotional well-being of refugees, who have suffered the most due to conflicts and wars. She is also currently working on a series of video stories on war crimes by searching for and telling the stories of people who have experienced them personally. Her main focus is to raise difficult and painful topics, thereby contributing to increased public awareness and the emergence of positive changes.