More than two thirds of the approximately 10 million Armenians live in the diaspora. In recent years, more and more young people want to discover their roots and take part in voluntary services. How do they view their “homeland”?

by Gloria Geyer

Yasmine points to an artistically decorated stone. “Do you already know Khachkar? These are our traditional Armenian monuments,” she says enthusiastically, looking at the works of art next to Noravank Monastery. Seeing the centuries-old stones here means a lot to her, she says. At home, her culture is not visible to the public. Yasmine lives in Istanbul, Turkey. In other words, the successor country to the Ottoman Empire, which committed genocide against the Armenian population in 1915. To this day, Turkey does not recognize the genocide, and diplomatic relations between the two countries are on ice. For this reason, Yasmine does not want to give her real name. She is too worried that she could come under pressure in Istanbul. In Armenia, however, she feels “very free,” says the 30-year-old.

Yasmine is one of around 200 to 250 participants with Armenian roots between the ages of 21 and 32 who come to their “home country” every year with “Birthright Armenia” (BRA) non-governmental organization for several months of voluntary service. There, the volunteers work for various organizations depending on their skills, interests and knowledge. According to the NGO, more than 2,600 young adults from 59 countries have taken part in the program over the past 20 years. The demand has risen significantly in recent years.

Diaspora network as a goal

Social anthropologist Tsypylma Darieva classifies this development as a global phenomenon in her book “Making a Homeland”. It is becoming increasingly attractive for young people to explore their own roots and at the same time gain work experience abroad. Organizations such as BRA play an important role in the cultural and emotional attachment of volunteers to Armenia. However, their political influence is limited, and the impact of their involvement is felt more at a local level, she says.

The aim of BRA for the volunteers is to get to know Armenia better – but also for them to exchange ideas with other participants and form a networked diaspora in the long term. Diaspora derives from ancient Greek and means “dispersion”. The term was originally used to describe an ethnic or religious group that had to leave its homeland involuntarily. The term primarily referred to the Armenian, Jewish and Greek populations. However, it is now also used for other migrant groups. Russia is home to the largest Armenian diaspora with more than one million people. Depending on the estimate, between 500,000 and two million ethnic Armenians live in the USA. In Europe, France is the country with the largest Armenian community, with more than half a million people.

Part of the costs of the stay are covered by BRA, which is funded by the H. Hovnanian Family Foundation (established in the US). BRA also helps with finding a relevant organization and offers language courses. In addition, weekly excursions are organized. This weekend, they will travel by coach for around two hours from the capital Yerevan to the south of the country. The program includes a visit to Noravank Monastery and a tour of the Magellan Cave. The atmosphere on the bus is exuberant. Some volunteers have already spent several months in Armenia, others have freshly arrived, just days ago. The newcomers are asked to come to the front of the bus and introduce themselves and their favorite Armenian dish. There is a big round of applause. For some of the volunteers, this is their first time in Armenia. They have no local family. Their grandparents lived in Turkey, Syria, Lebanon or Iran, for example.

23-year-old Karin Najarian from the US state of California also has Armenian roots in Syria and Lebanon, but feels connected to the Republic of Armenia. She walks almost reverently through the old stone halls of the monastery, which dates back to the 13th century and is now a major tourist attraction in Armenia. She studied architecture in California and was particularly interested in Armenian buildings. “Seeing some of the buildings in real life now feels special,” she says with a smile on her face after the visit. She can imagine spending some time in Armenia and continuing to work in the field of architecture. Armenian culture and architecture are an important part of her own identity, she explains. However, she is concerned that the Armenian monuments in Nagorno-Karabakh could be destroyed following the military takeover by Azerbaijan.

On September 19, Azerbaijani troops attacked the region (which is part of Azerbaijan under international law but was predominantly inhabited by Armenians) in a large-scale military operation. Within a few days, more than 100,000 Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians were forced to leave their homes and flee to Armenia. Social anthropologist Darieva observes that the second war over Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020 and now the latest major attack on the region are also preoccupying the diaspora. Many people are disappointed about the losses that Armenia has suffered. At the same time, however, the diaspora has established a more emotional connection to Armenia, she says. Many people organized themselves in refugee aid, for example.

“The diaspora should spread more awareness about Armenia”

Some of the volunteers also helped to care for the people arriving in Yerevan from Nagorno-Karabakh. They cooked food and packed parcels. Eric Babajanian was one of them. He says that being able to support his compatriots directly on site gives him a sense of fulfillment. The 26-year-old, who also comes from California, is in Yerevan for a whole year. In addition to his work in the country, it is also important to him to give his friends and acquaintances back home an impression of Armenia. “The diaspora should spread more awareness about Armenia, especially in these times,” he highlights. A friend of his is impressed by the pictures he shares on social media and now wants to travel to Armenia himself soon, Eric says proudly.

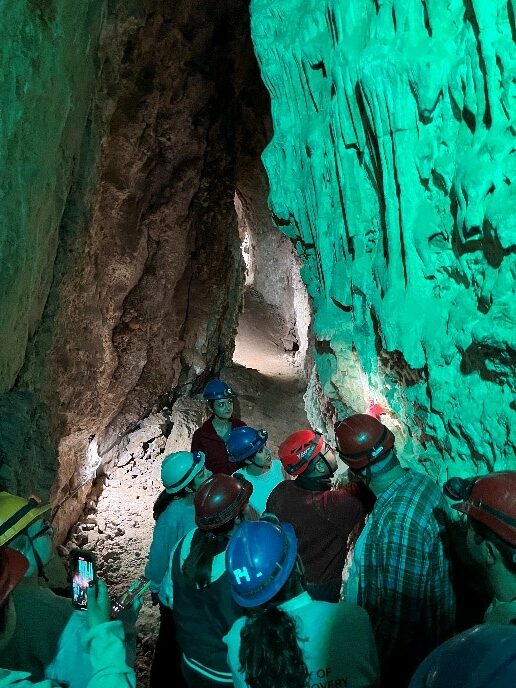

After the trip to the monastery, the group heads to the Magellan Cave. All volunteers are given a helmet with a headlamp and are instructed to look out for each other during the two-hour guided tour. Such activities are intended to strengthen team spirit, explains Diana Zakaryan, PR Specialist at BRA.

There is excitement before one section: the volunteers have to crawl around 35 meters through a narrow section. They encourage each other, but in the end the joy of having mastered the extreme situation together prevails. Karin and Eric hold hands and turn on their cellphone music. Together, they dance a traditional Armenian dance between the narrow rock walls, which they learned during their stay. This is probably the first documented attempt to perform the dance in a cave, they joke.

Volunteers help digging trenches

The weekend excursion carries a school trip vibe, but there are also serious moments. Many people in Armenia fear that Azerbaijan could attack again, but this time the south of Armenia and thus the heartland. This also concerns the volunteers. “Everyone is afraid of another war,” says participant Laura Nadjarian from France. The 30-year-old grew up near Paris. When she sometimes hears a bang in Armenia, she thinks at that moment that a new war could have broken out. Many of the volunteers have this feeling, she says. “You know it could happen any minute, but life has to go on,” she adds. Laura has already taken part in an excursion to a military training course with BRA. There, she dug trenches and positions with other participants. She also attended shooting training. “At least you can shoot if something happens,” she explains. Many people in Armenia have the idea of being able to defend themselves, at least in theory, against their heavily armed neighbor Azerbaijan. Organizations such as “VOMA” and “Metsn Tigran” offer military training for civilians.

Former volunteer Aram Kosian, who is taking part in the expedition again, also wants to be prepared in the event of an Azerbaijani attack and has taken part in Metsn Tigran’s military training courses. There he learned how to build a drone. Does he want to fight? The 25-year-old looks thoughtfully at the mountains surrounding the monastery and the cave. Every Armenian, including the diaspora, should take part in the training and be prepared in the event of an emergency, he believes. Aram is originally from Saratov in Russia and came to Armenia two years ago to do voluntary work. He stayed.

However, he believes that many people from the diaspora often have an overly positive view of the country from afar. That is why he is planning a project together with friends. They want to present a “realistic picture of Armenia” in videos on social media. They want to shed light on everyday problems, such as waste disposal. A first video shows how they encourage people on the street to dispose of waste properly in a playful hands-on activity.

One thing is clear to him: he wants to stay and raise his children in Armenia one day. “Armenia is the country where I can relax and put my mind at rest,” he explains. But it’s not just the volunteers who are shaped by the exchange. Diana Zakaryan started her new job at BRA shortly before the Azerbaijani attack on Nagorno-Karabakh. She felt a great deal of uncertainty at the time, but her work with the diaspora gave her stability, she says. Because once more she understood that Armenian culture will be preserved in the world, no matter what challenge the nation faces.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Gloria Geyer is a journalist in the digital editorial department of the dpa. Her semester abroad in Krakow sparked her interest in Eastern Europe, which prompted her to delve into Eastern European Studies at the FU Berlin. While focusing primarily on the Jewish history of Poland during her studies, her broader interests also included post-Soviet transformation and war reporting.

Gloria Geyer is a journalist in the digital editorial department of the dpa. Her semester abroad in Krakow sparked her interest in Eastern Europe, which prompted her to delve into Eastern European Studies at the FU Berlin. While focusing primarily on the Jewish history of Poland during her studies, her broader interests also included post-Soviet transformation and war reporting.