by Alexandra Duong

Is therapy a privilege, best reserved for times of peace? In talking to those who help Armenian soldiers and displaced people from Artsakh, it turns out that giving mental health support early and easily could be key to solving many other problems.

Humans, wrapped in layers of gauze. Dust and blood and tears. Black clouds of smoke, and houses in rubble: the horrors of war are often shown in images of visible destruction. The Nagorno-Karabakh wars were no exception. September 2023 added images of mass flight: heavily packed cars in convoys winding through the mountains, out of Artsakh, into Armenia. People holding onto each other, and their belongings, looking tired, looking lost.

But war and displacement also wreak havoc in ways that are harder to show. They devastate a human life on the inside. Some wail, some scream, but often, someone’s world crumbles in silence. The psychological wounds of fear, loss, pain and shock can be profound. They can result in conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression or substance abuse. Healing usually needs care, patience and professional mental health support. This can be very hard to come by, and there are barriers to getting help. This is true in times of peace – and much more so in a crisis.

The office of the Frontline Therapists is in a low, dark building, on the edge of Missak Manouchian Park, in central Yerevan. Frontline Therapists is a non-profit organization, founded by Arpe Asaturyan, a psychotherapist based in Los Angeles. According to their website, Asaturyan founded the NGO in 2021. She had volunteered and worked with injured soldiers and displaced families during the 44-Day War – also known as the Second Nagorno-Karabkh War – in 2020. They state their mission as providing “trauma-informed treatment to ex-combatants and any other people impacted by war,” as well as mental health education. They try to offer services anywhere in the country: “Many health and therapeutic services are scarce and substandard all throughout Armenia, and even more so in the communities and regions outside of Yerevan.”

On a warm day in early October, I sit down with Karine Bitar and Aida Taroyan in the Frontline Therapists’ office. Taroyan works at the organization as a therapist, Bitar is a social worker and manages the office.

As Taroyan tells me, she does not just offer a consultation, but therapeutic treatment that can last for a year or longer. Her clients mainly struggle with anxiety, PTSD and adaptation issues. Trauma is a connecting theme. She works with victims of war, soldiers, their families, and displaced people from Nagorno-Karabakh. Therapy, and other services the NGO offers, are free of charge. “In general, our health insurance doesn’t cover psychological treatment,” Taroyan says. In Armenia, one hour of therapy can cost 15,000 drams, around 40 US dollars, Bitar says. A “very good psychiatrist” could cost up to 95 US dollars per hour.

Last year, when people from Artsakh arrived, Bitar went with their director and a volunteer to one of the shelters. This year, they went to camps for children – one in the summer, the other during Easter – where Bitar offered a self-care class.

“They were still struggling in expressing their emotions,” she says. At the other camp, they worked with children and wives of fallen soldiers. She found the children in denial, crying, their mothers still “emotionally disturbed.” Bitar is in touch with families she met at the shelter, and checks up on them to see if they need anything apart from mental health support. “Most of them feel like they’re not ready to do therapy,” she says.

I ask about mental health awareness, and whether there is stigma associated with it. After the war in 2020, awareness around mental health rose, Taroyan explains. The need for psychologists was high, soldiers and their relatives sought psychological support. Many recently displaced people, mainly women, wanted to do therapy, Bitar adds.

“But of course there are still a lot of stigmas, especially out of Yerevan, in rural areas,” says Taroyan. They often work together with psychiatrists there, and the belief among many people is that psychiatric help is solely for the “crazy.”

But if mental afflictions are not treated, they can get worse over time. They can also bring more trouble, making it hard to get through the day, earn money, build a life, and maintain healthy relationships. They can devastate someone’s life. And their loved ones can suffer too.

Earlier the same day, I spoke to Ani Jilozian, who works at the Women’s Support Center in Yerevan. As director of development, she oversees fundraising. She also does research and advocacy. The center advocates on behalf of victims of domestic violence and offers them protection and support. Since 2020, they have seen reporting increase by 20 percent each year. Jilozian identifies three main factors to explain this: the first is greater awareness—more women actually report domestic violence. The second is better legal protection for victims. And the third? “War always exacerbates the issue of domestic violence in any given society, and Armenia is no exception to this,” Jilozian points out. A “militaristic rhetoric” would enforce traditional gender stereotypes, and “men and boys come back with PTSD and take that out on their loved ones.”

The effects of war on mental health seem to be complex, profound and long-lasting. As Jilozian explains, men and boys on the frontline are killed or traumatized. But afterwards, many women and girls need to be the family’s breadwinners, “they have to bear the burden of the war and the conflict for years and years to come.” And it does not stop there. The war will affect the mental health of the coming generations. “Armenians all know the term ‘generational trauma’,” Jilozian says, referring to the 1915 Genocide. “We’re told those stories. We know where our families come from,” she continues. This would also apply to this war: “It’s almost like embedded in our psyche as Armenians.”

A 2022 study, published in the International Journal of Psychiatry Research, examined the mental health effects of the 2020 Nargorno-Karabakh war. According to the authors, long-term and transgenerational effects of war have been studied, but immediate effects on mental health have not been explored as thoroughly. They found out that depression, anxiety and PTSD were more severe among people who were directly exposed to the war. These people were injured, for example, lost a loved one or their home. While the need for mental health treatment is high, “stigma and lack of resources remain barriers to Armenians seeking treatment.” A psychiatric illness could, they write, make it much harder to get a driver’s license or a job that pays well.

So there is the generational trauma of the Genocide, the effects of the decades-long Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, political instability and, possibly, further loss of Armenian territory. I ask Jilozian if she sees a growing awareness around these mental health problems or a tendency to push them away, because of the need of defending the country and staying operational. It is rather pushed away, she says, it is latent, but troubling. Most people are not being treated for trauma or mental health disorders, which perpetuates the problem. This, as she says, applies specifically to domestic violence, since victims and perpetrators have often grown up witnessing abuse themselves. “This is why we call it a cycle of violence,” Jilozian explains, “and until we come to terms with those mental health struggles, along with all of the other factors that are at play, it will be very hard to put an end to this.”

Later that day, in the office of the Frontline Therapists, I ask Taroyan and Bitar whether they notice lots of consequences of untreated mental health problems like domestic violence or substance abuse. Taroyan replies that domestic violence is indeed assumed to increase after a war. If mental health treatment is frowned upon, Bitar says, if it is considered a shame, it is normal to see the downside of that: physical, financial or verbal abuse, but also gambling or alcoholism. “We have a very serious issue of gambling in Armenia,” Bitar claims. Taroyan calls them “destructive coping mechanisms.”

However, Bitar also tells me that soldiers and others who come to the NGO for therapy want to get better. They understand how heavily the war has affected them mentally as well as physically. “None of them come with the idea that they’re weak and they’re embarrassed. It’s exactly the opposite,” she says. At the organization, they try to take in everyone seeking help, and to tailor the therapeutic approach to each client. One of them, Bitar notes, does not want to talk, so the therapist only does neurofeedback, a method that involves monitoring of brainwaves to give someone feedback on brain activity, which can help to reinforce a healthier emotional response.

Taroyan also gives seminars to educate the general public about stress management, grief or psychological first aid. I am wondering, though, what exactly the term “psychological first aid” refers to. “Maybe you will be surprised, but it has many common principles,” she says, referring to physical first aid: it should be provided as soon as possible, for example. The first hours are very important. Someone experiencing trauma can feel utterly helpless and unprotected. “We want to show the person that he or she is not alone,” Taroyan says. But the idea is not to do everything for a person in shock. Far from it: “We should try not to make them totally helpless.” They should not be stuck on a feeling of helplessness, which can lead to trauma development. “We should help the person to function somehow,” Taroyan explains, and this could be something as simple as getting a glass of water.

The need for mental health treatment only seems to grow, but barriers persist. As highlighted in the study, there is the stigma around mental illness on the one hand, and a lack of resources on the other. Finding and paying for a good therapist can be hard, much more so for displaced people from Artsakh, who are facing so many challenges at the time: they’ve lost their home, possibly their livelihood, and now struggle to build a new life, find a job, new housing, and a community.

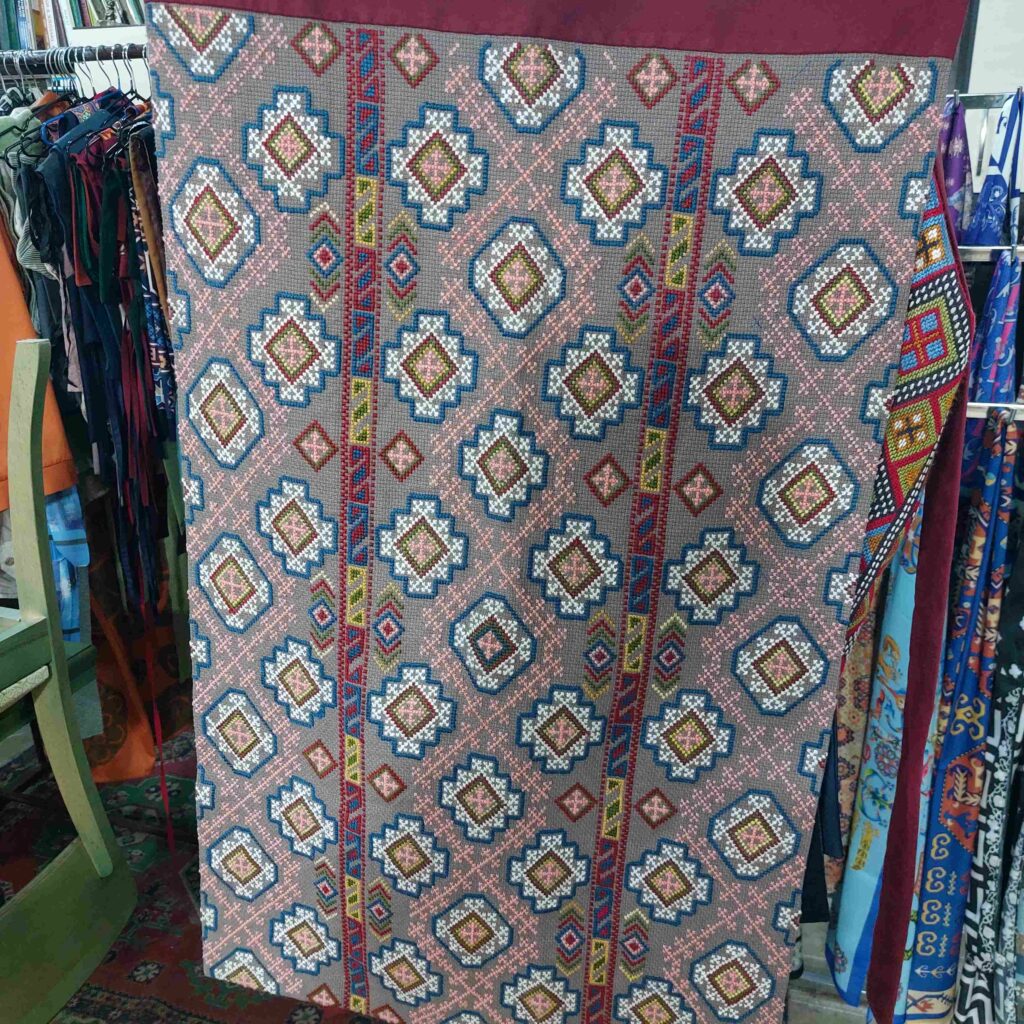

The Teryan Cultural Center is located in the Armenian National Library, along Teryan street in Yerevan, though it is somewhat hidden. After entering the library through a side door into a sombre foyer, you need to know where to descend a flight of stairs, to suddenly find yourself in a kind of Ali Baba’s cave: a basement room, illuminated, full of colourful tissues and objects. The women working there research and preserve Armenian culture. They create, for example, Taraz—traditional costumes with intricate embroidery. This year, the center received a European Heritage Award for their work with Armenian refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh. I get to talk to Anush Khojumyan, who has been working there for many years, as she tells me. She started with embroidery, and now organizes projects and does research. In 2020, they first provided humanitarian aid, such as food and hygiene items, to displaced people from Artsakh. Then they launched a program to teach pottery to refugees. Participants went on to teach these skills, in turn, to others who fled Artsakh last year. “In Armenian, it’s called ‘teach to future teachers’,” Khojumyan says. In addition to pottery, the program included felt-making and embroidery.

In 2020, they believed that a return to Artsakh was possible. That changed last year. “We decided to do something so they can make their own money,” she says. Moreover, pottery, embroidery and any handicrafts benefit mental health: “So they are making money and caring about their mental health, too.” Most participants are women, though there are some men, who are mainly interested in pottery.

When you have to start over, you might live from day to day, hope for a better future, and yearn for what you have lost. Studies have indeed shown the mental health benefits of handicrafts. But it might go beyond that. Khojumyan, who does cultural research, has learned from the participants as well. Artsakh, as she tells me, is known for its ornamented rugs and carpets. She shows me traditional aprons, embroidered with the region’s ornaments. Making one of these takes at least a month. “I think most of them love to keep their heritage,” she tells me: working with it, manifesting it, speaking about it. So they spin a thread, in a way, between their lost home and an uncertain future.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Alexandra Duong is a reporter, based in Paris. She studied history and economics in Mannheim (Germany) and environmental policy and regulation in London (UK) and went to journalism school in Hamburg (Germany). She focuses on environmental, health and foreign reporting.

Alexandra Duong is a reporter, based in Paris. She studied history and economics in Mannheim (Germany) and environmental policy and regulation in London (UK) and went to journalism school in Hamburg (Germany). She focuses on environmental, health and foreign reporting.