“Journalism is journalism no matter you are a conflict journalist, war journalist or specialized in writing about operas or economics or whatever: the task is to inform people as best as you can,” says German radio journalist Gesine Dornbluth in conversation with me.

by Victoria Andreasyan

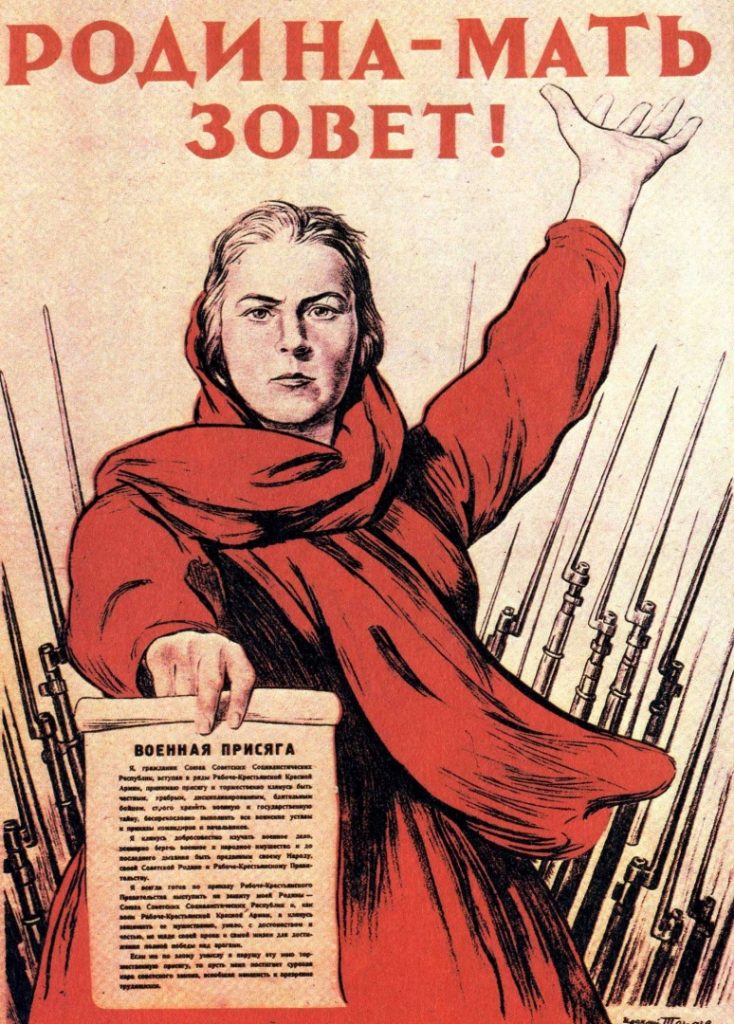

During wartime, propaganda is a powerful tool aimed at making people think in a certain way. As a rule, the creation of the image of the enemy, as well as negative stories about them have the purpose of recruiting more soldiers and keeping their morale high. Although the roots of propaganda go back centuries, the engagement of the media with it started during World War I. Initially, this engagement was in the form of featuring posters with strong messages. In Britain at the beginning of WWI, journalists were not allowed to report from the western front since the government was afraid that spies might read the papers.

This is why they passed a law to stop newspapers from printing information that could help the enemy or make British people feel unhappy about the war. The situation changed in 1916 when a British film was screened in cinemas about the Battle of Somme. For the first time people could see what was happening in the war.

War coverage in modern times

Nowadays, you can hardly surprise anyone with live footage from the front line. Moreover, war scenes in the media have come to replace the widely spread posters of WWI and WWII. While war propaganda is part and parcel of each government, the tools they use vary in democratic and authoritarian societies.

Four levels of propaganda are typically distinguished in the modern world. The first level features the “Big Lie”, which was personalized by Hitler and Stalin. The second level maintains that any sort of information can be presented, as long as it’s feasible. The third strategy consists of telling the truth, but in doing so, making sure to withhold the other side’s point of view. The last strategy insists on telling the whole truth, including all sides, and presenting both the good and the bad. The first level is mostly characteristic of authoritarian states, while Western societies usually adopt the last three, as people will generally not fall for the big lie, conditioned also by the presence of independent media in these societies. Nevertheless, often seeking to present both sides’ views and being committed to balanced reporting, journalists comfortably fall into the realm of bothsidesism, sometimes distorting the truth and assisting propaganda.

According to the 2022 survey by Pew Research Institute, 55% of American journalists polled have said that every side does not always deserve equal coverage in the news, while 44% believe that journalists should always strive to ensure equal coverage for all sides.

Bothsidesism in the coverage of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

The way the Western media reported on the 2020 war over Nagorno-Karabakh is a vivid example of equal coverage. In particular, most of them when talking about the events taking place on the opposing sides tried to refrain from showing personal attitudes and present similar situations from both sides.

“Some of the editorial policies were mostly designed in a way that both sides were supposed to be presented equally, although it was not always possible to do that, and one could see the disbalance when it came to the title of the article or its structure”, says Aren Melikyan, an Armenian journalist who has worked for several western media outlets during the 44-Day War. “Thus, if one of the parties reported about military attacks very often we were waiting until a similar report came out from the other side, and only after that published a piece on “both sides accusing each other in attacks.”

Aren notes that the reason for such coverage, besides personal biases of the editorial staff, was also the lack of deep knowledge about the conflict. “There is a cliché, which goes like ‘If someone says it’s raining, and another person says it’s not, a journalist has to look out the window to find out what is true’. But the thing is that in most cases even if you checked it and figured out it was truly raining, certain concerns arose whether to publish it or not because if so, the “balanced coverage” would be in question. On the other hand, the editorial staff was sometimes so far from the roots of the conflict that it wouldn’t even clearly tell whether it was rain or snow.”

Gesine Dornbluth agrees that international media sometimes lacks deep knowledge regarding the Karabakh conflict, and it obviously affects their coverage and the wording they choose. “In the case of Ukraine and Russia, it is more or less clear that you have Russia, which recently attacked a neighboring country without any reason. In Karabakh, you have a long history of conflict and you have this buffer zone, these occupied territories, which Armenia for good reasons didn’t want to leave but this makes it easier to say that it’s not clear who is the good one and who is the bad one.”

Context is important

Gesine Dornbluth thinks that balanced journalism might work if you are covering issues that are not a subject of propaganda. “But if you cover conflicts in the conditions of a massive propaganda and if you understand balanced journalism like “they say this, and he says that”, without any conclusion or any context, then it doesn’t work. In this case, you just fulfill the aim of disinformation that not only tries to give you wrong information but also attempts to make you believe that there is no truth at all,” says Ms. Dornbluth.

“We learned that balanced journalism is a good thing but during wartime balance journalism as such does not work if you just put together what both sides say. This is the wrong understanding of balanced journalism”. She is confident that even though there is a formula that information cannot be checked during wartime, it’s still possible to find out lots of things, and this formula cannot free journalists from bearing a responsibility. “It’s a little bit similar to when you buy medicine you always have on a paper something like risks, which you’d better consult with a doctor before taking it, and thus it’s not their responsibility anymore. And this is something that we cannot do in our job, saying ‘you know, I have this information but I cannot check it’. You can check it, it’s just a little bit difficult, and you have to wait.”

To stay committed to the values of impartial journalism and not to encourage the state propaganda of one of the sides, it is important to give the context. “You have to try somehow to put information together in a way that you have the possibility to properly make your conclusions. You – as a reader. And this is difficult of course during wartime because of disinformation, and I think what we really need to do is to give context to the information,” Ms. Dornbluth concludes.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Victoria Andreasyan is a journalist based in Yerevan. With a background in Middle East Studies, she started her career in journalism in 2010. The scope of her interests includes but is not limited to social issues, regional political developments, and the fight against disinformation and propaganda. Currently, Victoria works as a journalist and project coordinator at Infocom.am.

Victoria Andreasyan is a journalist based in Yerevan. With a background in Middle East Studies, she started her career in journalism in 2010. The scope of her interests includes but is not limited to social issues, regional political developments, and the fight against disinformation and propaganda. Currently, Victoria works as a journalist and project coordinator at Infocom.am.