6.2 million – this is the number of refugees from Ukraine recorded globally after 2022 February 24, as per UNHCR. According to UNFPA, the current population of Ukraine stands at 36.7 million.

by Diana Gasparyan

Russia’s full-scale invasion forced millions of Ukrainians to leave their homeland, with Europe recording 5.8 million refugees. The highest number of Ukrainians moved to Germany, which provided shelter to nearly 1 million refugees. These people, scared and confused, started seeking new homes, new life and striving for integration.

Western media report that Ukrainians are successfully integrating into the European societies and labor markets due to their education and many other traits, but challenges regarding language barrier, cultural and social differences, as well as psychological aspects persist. Another pressing question is how to find a “decent” job and a place to live, taking into account the migration situation and the pressure currently faced by Germany. “The number of refugees trying to get to Germany is too high at the moment,” German Chancellor Olaf Scholz recently said.

Thus, the German Government proposed steps to improve the integration of Ukrainian refugees into its labor market, calling on companies to loosen their German language requirements and offer extra training. The changes to the legislation were approved on November 1. According to Euronews, 196,700 Ukrainian refugees in Berlin are employed, but 42,000 of them work in positions that do not require contributions to social insurance. Over 100,000 refugees have completed language courses, with a similar number expected to complete their studies in the coming months. Those Ukrainians, like all other refugees who want to learn the language, try to adapt to a new life in Germany, find work, and confirm their qualifications, are receiving financial and other assistance by the Government.

Though… the flow of refugees is increasing, and the capabilities of host countries are limited.

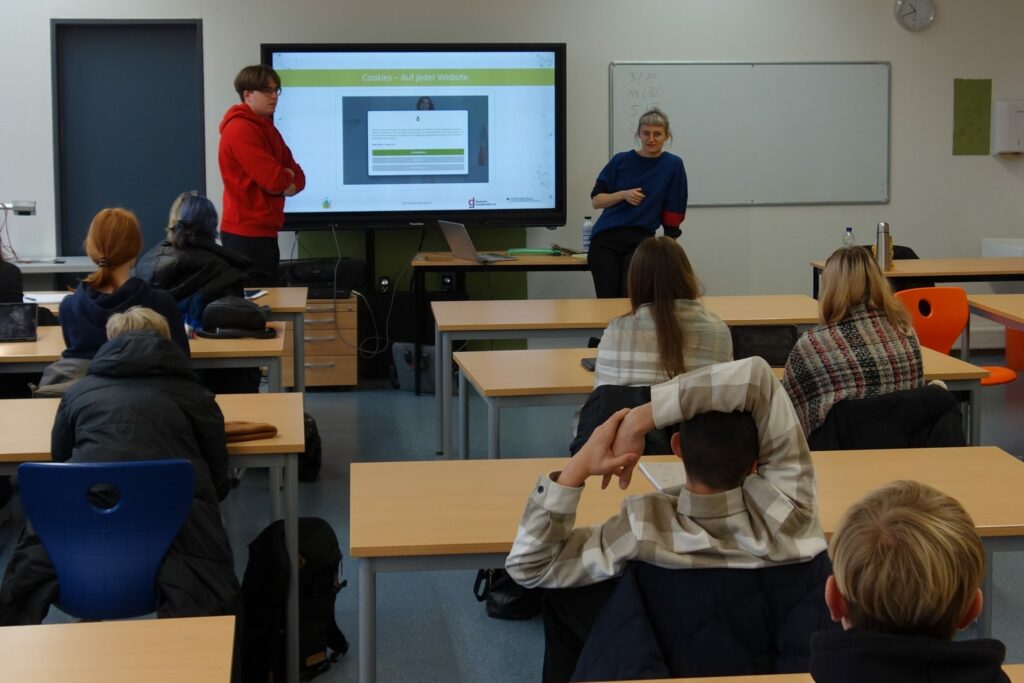

Christina Heiduck from Berlin-based Deutsche Gesellschaft organization conducts workshops, political education, and history courses for refugees – pupils and grown-ups. “It is sometimes difficult for people to integrate: so many are waiting to return to their homes,” she says.

Christina Heiduck: “After the war in Ukraine the number of refugees really grew. We try to help people get integrated, we talk about democracy and German history. We work with those learning German as part of integration courses. Obtaining German citizenship requires B1 level German proficiency and passing a test. However, there is another question: I don’t believe a lot of Ukrainians want to become German citizens. Many would like to go back to Ukraine.”

Refugees are mostly concentrated in Berlin, which is logical – Berlin is a city of opportunities. Nevertheless, “the Government tries to spread the refugees all over Germany,” Christina says. A question that may arise is whether Germany, particularly Berlin, feel increased pressure due to the refugee influx.

Christina Heiduck: “I think that pressure is felt in every place across Germany. It is a part of a big discussion presently. Some do not want to see many foreign people in their cities, fearing excessive changes in their places. This pressure is particularly noticeable in small areas. Many cite housing gap as the reason for refusing more refugees. Another thing is that refugee camps are really crowded, making them less than ideal places to live in.”

Compared to the previous year, the number of asylum-seekers in Berlin has increased by almost 32%. Roughly, 200 refugees arrive in Berlin every day. They are supposed to stay in an initial reception facility such as the one at the former Tegel airport only for a short time, before being relocated to accommodation elsewhere in the city. But available apartments are hard to come by, and some refugees have been stuck at Tegel for more than a year. Currently, some 4,000 people live there and a further expansion is underway to provide up to 8,000 places, as outlined by Deutsche Welle.

One of the Tegel staff members, who preferred to stay anonymous, shed light on the dire situation in the Tegel reception center. The facility houses people with various illnesses, wounded soldiers, women, and children, all having to stay there, with nowhere else to go. Things get even worse because of new flows.

“There are not enough German-speaking volunteers, even doctors in Berlin to help refugees with their needs. People live in Tegel just hoping to get provided with a place to live, or that the war ends so that they can return to Ukraine. Some children have not been going to school for almost a year because schools require registration. I don’t know where this is all going,” Tegel staff member states.

While conducting my journalistic research in Berlin I met Galina Kornienko. She had to leave her homeland behind like millions of other Ukrainians.

“In Berlin, there is money to support refugees, and there are programs, but the housing problem is huge. Even those with jobs and money are not able to find houses here. You might wonder “Why not move to other German cities?” I reply: where there are jobs, there is a housing problem, and where there is no housing problem, there is no job. Moreover, if you are registered in Berlin and seek employment elsewhere, your new employer must be interested in you enough to help you tackle the housing issue. Housing shortage is a serious challenge for Europe,” Galina says. She adds that integration programs are perfectly designed in Germany, but feedback mechanisms are not functioning well. “It will work, but it will take time.”

Galina got to Berlin on March 4, 2022, together with her partner and daughter: they had left their house in Hostomel, Ukraine, on February 25.

Galina Kornienko: “Our house was situated close to the military airport, which was taken over within the initial hours. On February 24, when it all started, we knew we were to leave due to constant rocket launches. Despite the media telling everything was fine in Hostomel, the reality was starkly different. Lacking bomb shelters or basements in our townhouse, the safest refuge became the toilet beneath the stairs on the first floor. Our hairdresser had also joined us, so there were four of us and five animals crammed into that small space. We spent the night there listening to the echoes of explosions. The following day we embarked on a 26-hour journey to Lviv — a trip that typically spans only 2.5 hours.

At first, we were thinking of moving to Bulgaria where friends were waiting for us. But we had a problem: the hairdresser with us was Belarusian. Therefore, we decided to head to Poland. Then a friend of mine in Berlin told us to leave everything and move to Germany, which we did. Initially hosted by a couple from Lithuania and Australia, we then found temporary accommodation with the second generation of Vietnamese refugees. The third hosts were Germans. And eventually, a month ago we just found a nice separate apartment.”

Galina currently works at a women’s health center — one of the oldest in Berlin. In Ukraine, she held the position of executive director in a prominent public organization before leaving. Meanwhile, her partner, a dentist, is learning German and preparing for exams scheduled in January. Once completed, she will submit the necessary documents for medical qualification validation, pass a medical exam, and start to work as a doctor.

Galina speaks about the attitude of Berliners towards Ukrainians. “It depends. Some used to ask why our country does not want to negotiate, and some expressed frustration, saying, ‘damn, we can’t go on vacation because of this war, prices have gone up.’ Now everything has changed. Also, some Germans think we are nationalists. There is a strong Russian lobby here.”

To my question about their plans to return home, she opens up:

“… The most difficult question one can ask. Many want to return, and others have nowhere to return. The hardest thing about living in Berlin is the language; now I’m taking German classes. However, language is my tool… I’m numb here,” she smiles.

“The world is tired of the war in Ukraine, Ukrainians fear that their fight will be forgotten,” numerous surveys indicate.

Christina Heiduck: “With the arrival of the first refugee group in Germany, as a person living here, I had the feeling that people really wanted to help, offer shelter. Everybody was shocked. However, as more refugees arrive, the situation ceases to be new anymore. People get used to the war being so close to Germany. They get used to it, and perhaps tired…”

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Diana Gasparyan is a journalist at Public Television of Armenia, where she prepares pieces for the First Channel News with a special interest in covering international events, particularly conflicts. Diana studied at Yerevan Brusov State University of Languages and Social Sciences.