2022. October. Berlin. Exhibition.

– What do you feel looking at these pictures?

– …

Silence was the answer to my question.

by Ani Torosyan

It took around 5 minutes for 54-year-old Alyona to start talking. Together with her grandchildren and daughter-in-law, she fled Kherson, Ukraine, at the end of February, with the hope of returning soon, but “in vain”. I meet Alyona at an outdoor exhibition titled “We Had a Normal Life: Ukraine 2006-2022”.

Through the tears she recalls how first they fled to Poland, stayed there with their relatives for about a month, then moved to Berlin, and it has been about a half year since they have been living here. “In the beginning we were thinking that this would be over soon, but now I don’t even know what to think. We just got used to this situation. These photos make me think one more time of the question I was asking myself for God knows how many times: ‘why did this happen?; how did this happen?’ We indeed had a normal life, and the last day of that normal life was February 23, but I am suspicious we will ever have one again.”

– What if I never go back to my house again? (A few minutes later Alyona asked, staring at me).

– …

This time it was my turn to keep silent.

“I came to photography because of the content I was witnessing in the streets of Cairo”

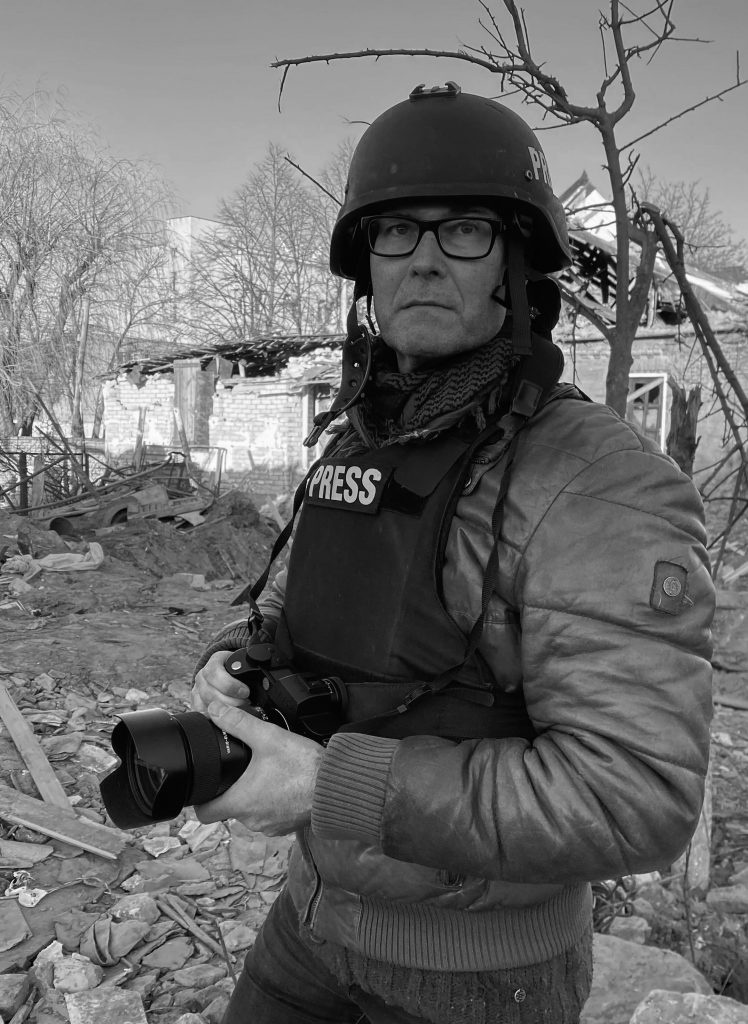

SEBASTIAN BACKHAUS, photojournalist specializing in crisis and war; Sebastian’s photos can be noticed among the ones featured at the Exhibition

That is why I bought a camera and started photographing

I started in 2011 while traveling to Cairo, Egypt, as a backpacker. Suddenly I came across street fights, but it was not in my plans to go there. So, a very extreme left-wing democratic movement was fighting against the police. Actually, what was going on there in the streets touched me a lot, and I thought I had to share it. That’s why I bought a camera and started photographing, and I came to photography because of the content I was witnessing in the streets of Cairo. I was looking for ways to share it with friends, and people in Germany, as that was a civil war, which was not being reported in Germany.

If there is no picture of the situation, it means nobody’s aware of it

I have been to Afghanistan, Karabakh, Iraq, Palestine, Niger, Syria, and Ukraine.

I’m seeking to give a picture that represents the world, so I hope to share it with the world. I know that it’s a very very high expectation, but I try. If nobody is witnessing what’s going on there in war zones, then nobody will ever know about it; in this sense, political decision-makers will never do anything to change it, because it is hidden. This motivation is driving me. I prefer to cover conflicts that are not very well covered, to report on areas about which only people suffering know. With my photos, I hope to bring change, with the exhibitions I aim to reach those who can donate money, help refugees, etc.

I feel empathy, fear, loss while photographing

I think empathy is very important not to become an ice block, because otherwise, you can’t get close to people, to support them – which is very important to me. Other photographers say ‘no, it’s not okay, you should keep your distance,’ but for me it’s the opposite. Sometimes I also have the feeling of fear, which is of great help, as it is a great consultant for me to know my borders.

I was growing up with “boom-boom”

I was growing up in Meppen, Germany, which is a little town on the border with the Netherlands, close to the weapon testing area of the German army. They were testing bombs there regularly, and one could hear the sounds. The windows of my parents’ house were shaking. When I got a bit older, I started asking myself “why are they doing this?”: that was my first reflection about the war. And today, war is a part of my life. It is something very normal.

I have to cope with all the things I have seen

One thing that helps me a lot is the opportunity to share what I see in war zones with others, because it’s not staying with me, it’s published somewhere. So, thousands of people can see that. The other method to cope with the situation is coming back to my German routine, meeting with friends, talking about what I was witnessing. Though it doesn’t always help, because sometimes sitting in my hotel room, editing photos I remember the situation, and I go through the same thing, and it is not easy, sometimes I even have to cry.

This is the story I remember while thinking of war

There are many stories that I will never forget, but the story of a 9-year-old Handa is very touching. She was a Yazidi girl that had been kidnapped by ISIS and held in Mosul, which was under the control of the Islamic State at that time.

Her family, her mother, were pretty sure that their daughter was dead, and there was not much hope that someone could come out of that situation alive. Three years later in 2017, the Iraqi army was liberating the city, and there was a big shooting about the liberation: they were shooting the building where the girl had been kept. After the attack, the girl managed to climb out of the building, started running through the ruins in the direction of the Iraqi army, and was finally freed. A day after she was united with her mother, I was there in their village and saw them holding each other.

“When the war stops appearing in the headlines, it doesn’t mean there is peace: it is just nobody reporting about it”

TILL MAYER, Award winning photojournalist, Social photographer

I don’t want to show people victims all the time

Three weeks ago, I was in a small village close to the city called Kupiansk. It was just liberated from Russian troops. And there were still dead bodies of Russian soldiers, plastic bags on the road and destroyed houses around. I came across a lady who buried her son killed by Russian soldiers. There was a big hole from the grenade in front of her house. She was all alone and didn’t have the energy to bury her son in the cemetery, so she put the body in that hole.

And she did it the day before I arrived. When I came, she had just finished the wooden cross. She was so shocked by this situation that she was completely without emotions. The lady told me everything in detail, but I knew that in 3-4 more weeks she would completely collapse, as at that moment if she allowed herself to feel something and have emotions, she would have gone crazy. Of course, a situation like this is indeed something that affects me as a photographer, and there is not so much hope you can find in such a situation because normally when I photograph people, I also try to show their strengths. I don’t want to show people all the time as victims.

How I started!

I was a schoolboy, 16-17 years old, working for a local newspaper to get some extra money. I was doing stories about little clubs and organizations in the place where I went to school, but I was a very lazy photographer. I screwed it up 3-4 times when taking photos, and my boss said that if it continued like that, I wouldn’t be able to deliver good photos, and it would be the end of our cooperation. Once he said he would show me the most important thing, and it worked out: after that, I got better and better. But it took me around 10-15 years to find my handwriting as a photographer.

My grandma used to tell that war is an evil thing

When I was 9-10 years old, I started to get interested in politics and read a lot about WW2. We had a book on the bookshelf where you could see all the photos from the holocaust, of course, my parents didn’t give it to me as I was too young, but I found it, and they touched me a lot. My grandma had experienced war and she always used to tell me that war is an evil thing. But somehow, I also wanted to know what war is, and what it means. As a journalist, when you make stories about people, it is good you understand what they’re going through, and the only way to understand is by going to war. It’s one of the reasons that I went to Bosnia when I was 21. There were a lot of little humanitarian transports from small NGOs, I jumped on one of them, and ended up there. That was the first time I was in the war. I sent that story to the Red Cross and started cooperating. Four months later I was in Luanda, Africa. And this is how all this started.

Usually, there was always war going on

It is just that only people do not speak about it anymore. I started reporting when the war in Angola started in the 90s, and it was a very crazy war. I went to Somalia, Liberia, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Congo, also I was reporting from the Middle East, I was in Palestine, Iraq and pictured the conflict zones in many areas.

When the war stops appearing in the headlines, it doesn’t mean there is peace. It is just nobody reporting about it. To me, this is very dangerous. For example, now Syria is not in the headlines anymore, but still, there is no peace. Same is with Iraq or with the Central African Republic, which is a very dangerous place, but nobody’s speaking about it, though there is a conflict going on. People living there have the right to raise their voice, get heard.

I don’t fear so much, to be honest

I’m very aware of the security situation I am in, but it’s not that I feel fear. Maybe something is wrong with me. For example, when you go to a battle place at night with a car that has no lights, and you know that when the Russians see your car, you are dead, that’s it. Of course, you have a special feeling, but it’s not really scary.

The only thing that I am afraid of is causing problems to people with my interviews and photos, because very often I am in areas where there is no democracy, like in Africa. There are lots of strange people around looking at what you’re doing. I don’t want to put them in danger. You must be very careful about what kind of photos you take.

As a photographer, you must understand it is not your fault

If you want to become an oncologist, for example, and you have an eight-year-old boy in front of you, you know exactly as a doctor that this boy will die in three months, he has no chance, of course, you have empathy for him because otherwise, you’re not a good doctor. But you must be able to close the door at home, you must be able to draw some kind of border to protect yourself. And if you’re not able to do that, to distance yourself as a war photographer then you shouldn’t do the job. You must be able to also have your own life and understand that it is something that you cannot change and allow yourself to enjoy life. Of course, it’s not always working, and sometimes you get depressed since this eight-year-old boy died. A long time ago there was a drought in Ethiopia. And it was terrible to see people, children dying in this 21st century because of a lack of food. After that, I stopped going to conflict zones for one year.

This really shocked me, touched me, and still does

When I was in Iraq, I did a small film clip together with an Iraqi colleague. In the beginning, we were just too professionals working together, it was just a business relationship but somehow, we made friends. Actually, I wasn’t sure who this guy was. I was working for the International Red Cross, and it was through me he got his salary, this might have been the reason he was nice to me. But on the last day, when I was to leave the country after finishing my mission, he came to me and gave me a very beautiful present: a very old plate from kingdom times. So, it was something really rare. He knew that he would never see me again, and it was not that he wanted to have a good relationship for the next job; he really wanted to show me that he liked me as a friend, and he got killed soon after that.

This is one of the most beautiful photos I have ever taken

When you are a photographer, in the end, you are never satisfied with your work, but I have some shots that I think are not too bad, and they touched people a lot because this is the mission.

The picture that I like is now on the cover of a new book. You can see a soldier taking his girlfriend in his arms in front of ruins. He is not only a soldier, he is a good friend of mine, Sasha from Kharkiv. So, I went there in April when there was a lot of fighting. I was there not only for the story but also to show my support to my friend. Sasha managed to get his first day off from the frontline to see me. Julia asked me: “Can you take a photo of both of us, as a souvenir from hard times?” I said: “Okay, let’s do it.” By the time I was photographing, they already forgot about me, and that was a moment full of joy actually, but you can see all the ruins as well. And it became one of the most beautiful photos I have ever taken.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Ani Torosyan, is a freelance multimedia journalist, filmmaker based in Armenia. She got her master’s degree in Multimedia Journalism and Media Management at GIPA (Georgian Institute of Public Affairs). It has been more than a year that Ani works at Journalists for Human Rights NGO, making video and photo stories mainly about convicts, casualties of war and refugees. She is also a freelancer at Chai-Khana.

Ani Torosyan, is a freelance multimedia journalist, filmmaker based in Armenia. She got her master’s degree in Multimedia Journalism and Media Management at GIPA (Georgian Institute of Public Affairs). It has been more than a year that Ani works at Journalists for Human Rights NGO, making video and photo stories mainly about convicts, casualties of war and refugees. She is also a freelancer at Chai-Khana.