by Gevorg Tosunyan

The format of the traditional Friday meetings in the Armenian community building in Berlin has recently changed. As a rule, representatives of the Armenian community gather here to communicate and discuss various issues.

After September 19, when the Azerbaijani Armed Forces attacked and carried out an ethnic cleansing in Artsakh [Nagorno-Karabakh], people began to use Berlin community center as a platform for charity programs. After the Azerbaijani military operation, almost all of the estimated 120,000 ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh have fled west to Armenia.

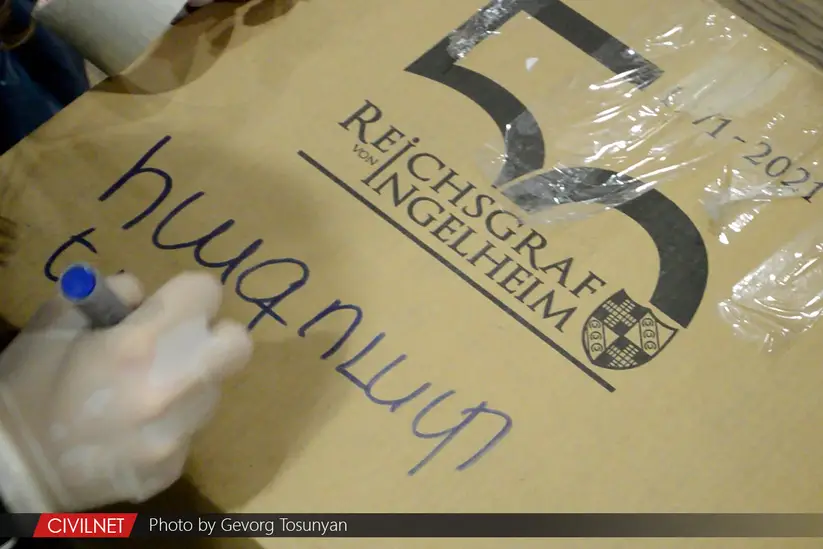

Nowadays, many Armenians living abroad try to help them, as Lilit Kocharyan does in the Armenian diaspora center in Berlin. She actively contributes to the German-Armenian charity organization Kamurdsch-Brücke e.V.

“We issued a statement aiming to collect some clothes, bedding, and hygiene essentials to send to Armenia. Many Armenians and Germans responded,” says Lilit Kocharyan.

In the Armenian community building, we also met two Germans. They had learnt about the situation in Artsakh from the German press and brought various things for the children of Artsakh in order to transport them to Armenia.

Lilit is also engaged in civic activities with local Armenians. They held a number of protests and sent letters to the German state authorities.

“Germany treats Armenia as an emerging democratic state, which may have a pro-European bias. However, in economic terms, Armenia is an uninteresting country for Germany and for all of Europe,” Kocharyan observes.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan has energy resources, which were much more important for the EU during the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Is German society aware of the Karabakh conflict? According to Lilit, German society is mostly unaware.

“Under each news story, there was a disclaimer about the conflict. This disclaimer included a standard text, asserting that Artsakh belongs to Azerbaijan from the point of view of international law but is inhabited by Armenians. There’s no mentioning about the the NKR’s independence referendum held on December 10, 1991.”

However, according to Lilit, during the attack of September 19, perceptions suddenly changed.”

“During the 2020 war in Nagorno-Karabakh, they thought that this was the territory of Azerbaijan, avoiding criticism; nowadays, this perception has already changed. The narrative in the German press changed dramatically. The German press was more objective; they clearly identified Azerbaijan as the aggressor. Some media sources used the term “ethnic cleansing” and some even used the term “genocide,” Lilit points out.

According to her, this reality has not yet led to any practical steps; for example, Azerbaijan has not been subjected to sanctions.

“I don’t think it depends on Armenia; it depends on Germany’s own political interests. I believe it is also connected with Russia and Ukraine. It seems to me that for the first time they clearly realized that Russia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan are waging a joint war against Armenia and Artsakh, and that Armenia is not an ally of Russia,” Lilit says.

Armenian-Azerbaijani relationships are getting more and more complicated. We asked Nadja Douglas, a political scientist and a researcher at the Centre for East European and International Studies, to describe this conflict.

She believes that neither Azerbaijan nor Armenia have been ready to compromise regarding Nagorno-Karabakh.

“The problem now is that Azerbaijan has created new facts: the seven provinces have been handed back, and Nagorno-Karabakh has become Azerbaijani territory. It would have been now the turn of Azerbaijan to finally provide certain provisions for the special status of Nagorno-Karabakh, but Azerbaijan wasn’t ready to make any concessions in that regard. I believe that if they want to achieve sustainable peace and live peacefully together in that region, they should, at some point, find a political and peaceful solution”.

Nadja Douglas says that Azerbaijan has to negotiate with the representatives of Nagorno-Karabakh to provide them with some sort of status, to grant them minority rights, and to ensure their security.

Nadja Douglas says that Azerbaijan has to negotiate with the representatives of Nagorno-Karabakh to provide them with some sort of status, to grant them minority rights, and to ensure their security.

On the other hand, the matter also pertains to the so-called Zangezur and Syunik corridors from an Armenian perspective. There is a significant fear among Armenians that Azerbaijan could create a sort of territorial status, exerting full control over these corridors.

“Azerbaijan eventually aims to have this connection for railroads, transit routes and gas plants to link western Azerbaijan and Turkey through Nakhijevan. Many of these aspects should be part of a peace agreement so that Armenians can at least be safe in the future. The top priority now is securing Armenia’s safety within its internationally recognized borders,” Nadja Douglas highlights.

By the end of September, over 100,000 Armenians had fled Nagorno-Karabakh and found refuge in neighboring Armenia.

***

The Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict is mainly over Nagorno-Karabakh, an enclave with a majority Armenian population incorporated arbitrarily in Azerbaijan during the early Soviet years. Following the fall of the USSR in 1991, Armenia and Azerbaijan fought two wars over Nagorno-Karabakh in 1992-1994 and 2020. Pogroms against Armenians in Azerbaijan and mass displacement of over one million people in both countries continue to poison relations. On September 2, 1991, Nagorno-Karabakh seceded from Soviet Azerbaijan to preserve its population’s right to life, formed democratic governance institutions, and continued to self-govern until September 2023.

On September 19, following a nine-month medieval siege of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan launched a massive offensive on the enclave, overwhelming its meager self-defense forces within 24 hours. The European Parliament called the attack “unjustified” and a “gross violation of human rights and international law”. Armenia was unprepared militarily and could not help the enclave. The fewer than 2,000 Russian peacekeepers stood aside as Azerbaijan’s forces bombarded civilian and military targets indiscriminately. Azerbaijan completely ignored toothless Western appeals to halt the offensive.

This article was published within the frames of “Correspondents in Conflict” Project,

implemented by Yerevan Press Club and Deutsche Gesellschaft e. V. The Project is

funded by the German Federal Foreign Office within the “Eastern Partnership Program”.

The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the implementing partners and can in

no way be taken to reflect the views of the Federal Foreign Office. #civilsocietycooperation

Gevorg Tosunyan, a graduate of Yerevan State University’s Journalism Faculty, has been actively engaged in journalism since 2011. He initially worked at “A1+” and iravaban.net, before joining CivilNet in 2017. During his tenure at CivilNet he extensively covered the Second Karabakh War, and following the war in 2020 he reported on almost all escalations on the border. He personally visited the villages close to areas of military clashes.

Gevorg Tosunyan, a graduate of Yerevan State University’s Journalism Faculty, has been actively engaged in journalism since 2011. He initially worked at “A1+” and iravaban.net, before joining CivilNet in 2017. During his tenure at CivilNet he extensively covered the Second Karabakh War, and following the war in 2020 he reported on almost all escalations on the border. He personally visited the villages close to areas of military clashes.